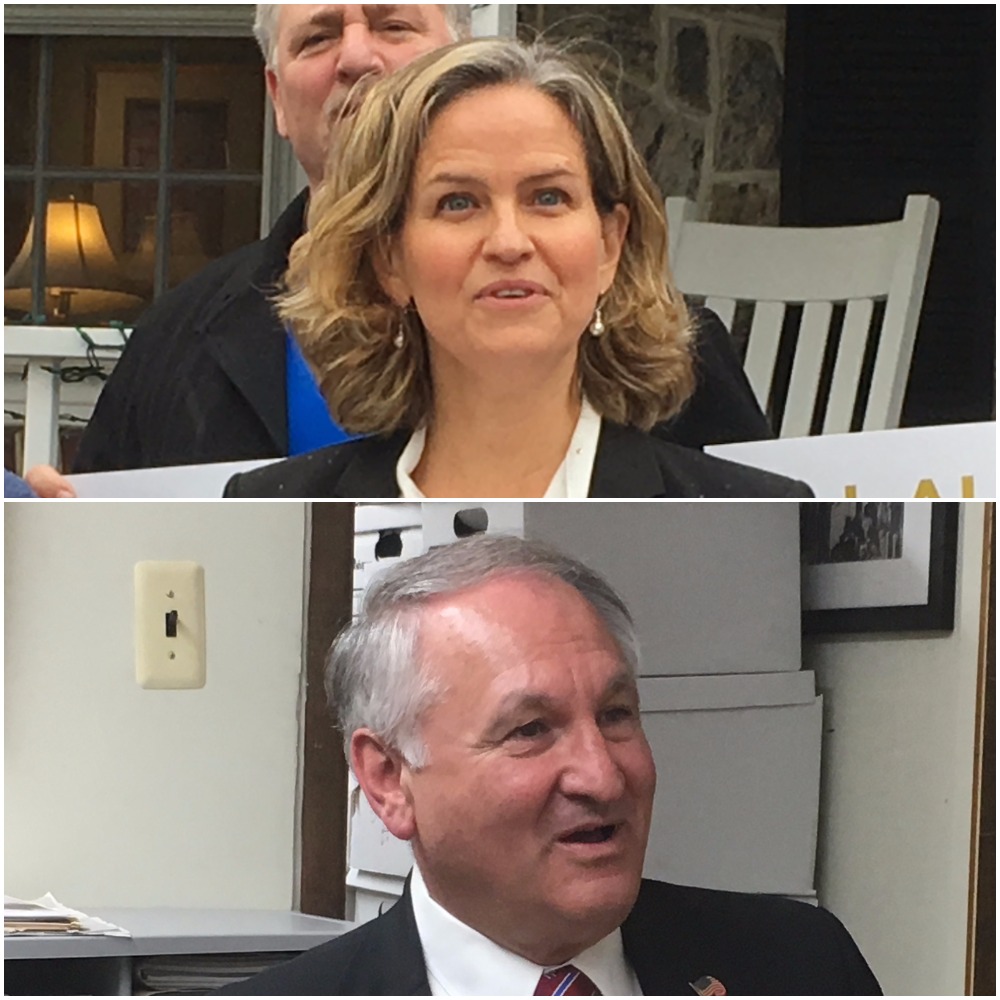

Laura Curran and George Maragos agree that Republicans have created problems for Nassau County: an unequal property tax system, troubled finances and political corruption scandals.

But in sit-down interviews last Thursday, the Democratic candidates for county executive differed — sometimes subtly, sometimes substantially — on how to address them as their party’s Sept. 12 primary approaches.

Maragos, the eight-year county comptroller who became a Democrat less than a year ago, said he lacks faith in Curran’s ability to find and implement real solutions, especially when it comes to equalizing Nassau’s troubled property assessment system.

“She doesn’t have a clue what the issues are, let alone how to fix them,” Maragos told Blank Slate Media.

But Curran, a four-year county legislator from Baldwin, said she is the “true Democrat in this race” who offers a “stark contrast” to Maragos’ Republican past, which will make a difference in a low-turnout primary.

Curran has called Maragos a “yes man” for Republican County Executive Edward Mangano, who is not seeking a third term after pleading not guilty to federal corruption charges. Maragos rejects that claim.

“It doesn’t matter what community I go to, what the demographics are, what the politics are — people are talking about corruption and about being fed up with corruption,” Curran told Blank Slate Media.

About 9 percent of registered Democrats voted in their 2013 primary for county executive, Newsday reported at the time. Nassau had 389,209 active registered Democrats as of April 1, according to the state Board of Elections.

This year’s winner will face Jack Martins, a Republican former state senator whom the Nassau GOP has tapped to replace Mangano.

Maragos was the first candidate to launch a county executive campaign last September, when he switched parties after being elected comptroller alongside Mangano in 2009 and 2013. Curran, the first woman to seek Nassau’s top elected office, declared her candidacy last November.

Maragos has cast himself as a political outsider, calling Curran the “puppet” of Nassau Democratic Chairman Jay Jacobs, who gave Curran the party’s support after Maragos sought it.

Curran and Jacobs have countered by pointing to Maragos’ previous conservative political views, such as his opposition to abortion rights and the Affordable Care Act, and a 2011 remark comparing same-sex marriage to people wanting to marry their pets.

Maragos said he apologizes “deeply” for his “inappropriate” comments, and that his nieces convinced him he was wrong to oppose abortion rights.

Maragos’ campaign has some 300 volunteers who are working to court Democrats who do not typically vote in primaries, he said. Curran, meanwhile, has a “robust field operation” that includes eight campaign organizers and many volunteers, she said.

Maragos has courted ethnic minority communities and eschewed endorsements from unions and public officials, while Curran has touted support from those groups as proof that she’s the best choice.

Both Democrats think it’s imperative to move away from Mangano’s policies, but they have divergent approaches to fixing the county’s beleaguered property tax system.

Taxing property based on market value and making annual adjustments would create a more accurate system and largely eliminate tax challenges, which are expected to cost the county about $60 million this year, Maragos said.

Maragos would revalue each county property annually using software that would make automatic adjustments to each property based on recent real estate sales, he said.

That would remedy the shift in the property tax burden from homeowners who challenge their tax bills to those who don’t that Mangano’s policies have caused, Maragos said.

“I’ve seen it from the inside, and I know how to fix it,” Maragos said. “And it’s easy to fix — it’s not difficult.”

Responding to Maragos’ charge that Curran lacks the know-how to fix the assessment system, Curran spokesman Philip Shulman said the comptroller ran with Mangano in 2013 “on a platform of fixing the assessment system and they’ve actually made the problem even worse.”

Maragos said he predicted the $1.7 billion tax burden shift — which Newsday documented earlier this year — in 2011 and spoke out against the policies that caused it.

Annual reassessments would be “ideal,” but too expensive and less realistic than a three- to five-year cycle, Curran said. But she said an assessment system based on homes’ fair market value “makes the most sense.”

To Curran, the solution lies in resolving discrepancies between the county’s Assessment Department and the Assessment Review Commission.

The former lacks sufficient staff and should be led by a credentialed assessor, Curran said. The acting assessor, James Davis, got the job in 2011 after working in the department for 26 years, Newsday reported then.

The commission, which reviews all assessment appeals, uses a method of determining property values that is different from the Assessment Department and more favorable to homeowners, Curran said.

“If so many people have grieved [their assessments] and others have not, they are completely out of proportion, and unfair,” Curran said.

In his 2012 run for U.S. Senate, Maragos opposed illegal immigration and said in a debate that he would report an undocumented immigrant if he learned one was working in his home.

But he now stands to the left of Curran on what role the county should play in federal immigration enforcement, an issue Martins has made part of his platform.

Maragos called for a unified countywide policy that protects undocumented immigrants’ due process rights. He said the Nassau Police Department should not honor administrative requests to detain immigrants who are arrested for unrelated, low-level crimes, as it does now.

“It violates due process and it should not happen in Nassau County,” Maragos said.

“Sanctuary cities” such as New York City, which limit cooperation with federal authorities, have similar policies.

Curran said the Police Department should continue to refrain from asking people about their immigration status, emphasizing the importance of trust between officers and immigrant communities.

But even when pressed, she would not say whether police should continue honoring administrative detention requests.

“There needs to be trust between the police and the communities in order for them to do their jobs,” Curran said. “On the other hand, if you are a violent criminal, there is no place for you in our society.”

Curran has criticized Maragos and Mangano for claiming Nassau has a budget surplus as it continues to borrow money for operating expenses.

County officials must “call a deficit a deficit” and find savings to balance the budget without borrowing, she said.

Though Maragos has defended the county finances as stable, he said he would follow a mandate from the county’s financial control board, the Nassau Interim Finance Authority, to produce a balance budget without borrowing.

He noted that he has criticized Mangano for unnecessary borrowing.

Some of the candidates’ anti-corruption plans overlap. Both support term limits for the county executive and legislators, and an inspector general, appointed by an independent committee, to monitor contracts, a proposal Democrats have pushed for two years.

Maragos said he would also push for an independently appointed procurement director who would ensure that contracts follow county rules. Mangano has hired a procurement compliance director who serves at his pleasure.

Asked whether she supports that idea, Curran said it is “something to think about.”

Both candidates want to restrict political donations by county vendors — Maragos would ban them outright, while Curran would cap them at $5,000.

Maragos also supports public financing of elections to reduce the influence of big campaign donors over local elections.

Curran has also proposed “tangible” changes to insulate government from politics, she said, such as leaving her name off signs at county facilities.