You could be married for 60 years, but your first love lasts forever.

Though that may sound like the tag line for a blockbuster romance flick, perhaps in the vein of “The Notebook” or “Titanic,” it is the subject of Great Neck resident and Fordham English professor Eve Keller’s 2012 book, “Two Rings: A Story of Love and War,” and the tale is no work of fiction.

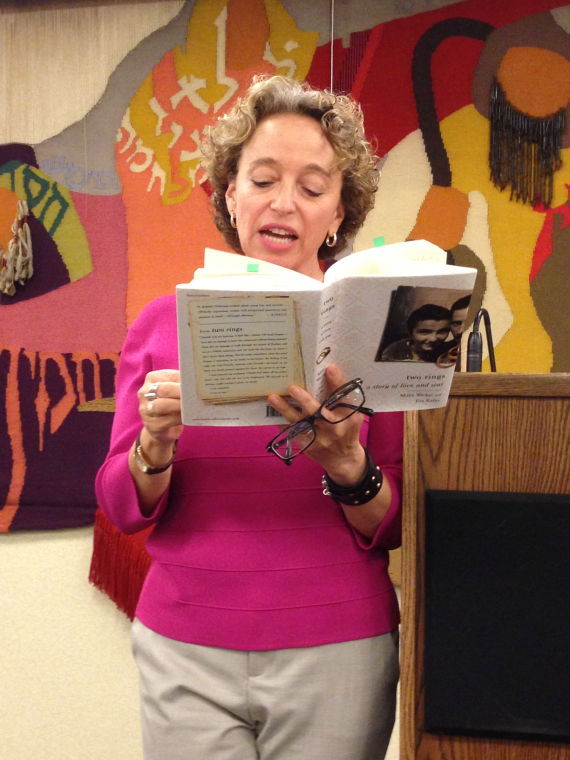

Keller, who lives in the Village of Thomaston, gave a lecture at Temple Sinai in Roslyn Heights last Thursday to tell the story of “Two Rings,” which follows Holocaust survivor and Great Neck resident Millie Werber as she carries two wedding rings – her own and that of her late husband, Heniek Greenspan, a Jewish policeman who was killed by the Nazis after his betrayal by another Jewish officer.

Werber carried the two rings through slave labor in German factories, two death marches, captivity at Auschwitz, and eventually, her emigration to America.

Keller said although she typically makes speaking engagements alone, she wanted Werber to greet the Temple Sinai community for the lecture because she lives so close to the temple, but the subject of her book had been sick that afternoon and was not in attendance.

Keller met Werber through Werber’s son Martin, whom she knew from the committees they worked on with at Temple Israel, where they are members. He suggested Keller tell the story his mother had only recently shown an interest in sharing.

“She hoped for a book with a lot of heart, and I certainly tried to give it a lot of heart,” Keller said.

Werber grew up in the central Poland city of Radom and was 12 years old when war broke out in 1938, Keller said. At 14, Werber and her family were taken into the ghetto, and at 15, she began work at a forced labor factory, where Greenspan, 12 years her senior, worked as a guard.

Keller said Werber was one of the most beautiful girls in her village, receiving so many potential suitors that the goldsmith who made their rings didn’t want to give it to her because he wanted to marry her instead. Greenspan, too, was among the most desirable young gentlemen in the neighborhood as well, so good-looking that Keller said Werber was at first too afraid to tell him how she truly felt.

Greenspan worked as a guard in the labor factory, which had been considered safer than the ghettos, and was killed as a result of a plot guards working in the ghetto had set to replace those in the factory, Keller said.

Before he was arrested, Greenspan gave his ring to Werber to remember him by, and she hid it from the Germans for the rest of the war.

But Werber kept the story from her family for much longer.

Werber, who was 16 at the time, was married to Greenspan for a little more than a month, and after the war ended, married Jack, her husband of 60 years.

But every so often, Keller said, Werber would sneak away to her bedroom, open a box she kept hidden at the back of her closet, and take out the rings, secretly remembering the love she and Greenspan shared that ended all too soon.

“For the 60 years and more after the war, she never told anybody about her marriage to Heniek, especially not the importance and endurance of the memory of her first love,” Keller said.

Jack, a survivor of the Buchenwald concentration camp to whom she was married for 60 years, was eager to share his experiences. He worked with Queens College sociology professor William B. Helmreich on his memoir, “Saving Children: Diary of a Buchenwald Survivor and Rescuer,” which was released in 1996.

Over the years, Werber kept much of her own story to herself, out of fear Martin and her other son David would feel betrayed at the idea of their mother being married to anyone prior to their father, much less still having fond feelings from the marriage, Keller said.

But when Jack died in 2006, and at Martin’s insistence, Keller said Werber started to come around to the idea of telling her story.

“Millie started to think about her own mortality,” Keller said. “She started to think about the possibility of her dying without her sons knowing why she stayed silent for so long. She started to read second-generation Holocaust books from the children of Holocaust survivors, and Millie had a hard time with this. The stories were being told as they were filtered through the troubles and concerns and obsessions of the second generation, and she needed to claim to story for herself.”

Keller interviewed Werber for nearly a year, and Martin arranged to have their conversations recorded and transcribed to ease the writing process. Keller said she served as Werber’s “intermediary,” telling her sons the story through Keller for reproduction in print.

“She didn’t particularly want her sons, if she died, not telling her story,” Keller said. “She was worried that her sons would think that because she stayed silent, it was because she had something shameful to hide. She didn’t want that possibility. She wanted them to know that she did have a secret, something that she treasured, and it wasn’t something she was ashamed of.”

Keller said “Two Rings” does not offer a sense of what it’s like to live in a concentration camp, like “Saving Children” did, but portray what it’s like to for a teenager to be in love amid grim circumstances, and appeal to an audience that may not regularly take an interest in the holocaust.

“My imagined audience was the non-Jew from Nebraska. That’s, for me, how I envisioned my audience, somebody who was foreign to this,” Keller said. “But I’m foreign to it, too. People say when you write, write what you know. What do I know? I don’t know anything about this, but neither does the non-Jew from Nebraska and so what I tried to do was figure out how I could make bridges from my perspective and Millie’s experience, between my imagined non-Jew from Nebraska’s perspective and Millie’s experience, to make her story matter beyond the immediate environment.”