Walter Crosby vividly recalls the first call he responded to as a chief of the Mineola Fire Department at the scene of accident on the Long Island Rail Road crossing on Herricks Road.

A van with six teenagers was struck by a train on the tracks. One had been thrown from the van and impaled on the third rail. Only one of the six young victims survived. And Crosby knew all of them personally.

“My heart fell down. All those kids were associates of my kids,” Crosby said. “I had a lot of trouble with that call because of the horrific scene we confronted.”

It was the worst call that the 73-year-old Crosby ever had to go on in a career of volunteer service that spans 50 years. But it’s an indication of the kind of selflessness that has characterized a life spent as a member of the New York City Police Department and as a Medicaid fraud investigator, along with his volunteer efforts.

He originally joined the department as a member of the Mineola fire volunteers’ Truck Company No. 2 in December of 1960. He rose in the ranks to become a lieutenant in that company from 1966 to 1970, and served as captain of the unit from 1970 to 1972.

He achieved the rank of second assistant chief from 1981 to 1983, and then first assistant chief from 1983 to 1985, becoming chief for a two-year term in 1985.

Crosby was recognized as Fireman of the Year in 1977 and was given the Town of North Hempstead Firematic Service Award in 2008.

“I was actually there during the pioneering years,” he said.

In his early days as a chief, there was no home alert system for the volunteer firefiighters in the community. He had the fire sirens turned off when he was chief, in deference to residents who had medical issues, and established the home alert alarms. Some residents objected, but the new system worked admirably.

“The home alert systems blew us out of bed,” he recalled, smiling.

When he was chief, he didn’t ride in a chief’ car. He had a detachable flashing light for the top of his car, a citizen band radio and a walkie tallkie.

He improved conditions in the fire house itself by installing air conditioning in the building.

“It was a time when we were looking for change,” he said, recalling that he always enjoyed a cooperative relationship with the village board.

His volunteer work in the community also included a term as commissioner of the Mineola Little League.

Meanwhile, his full-time job through the early 1980s was in the NYPD, where he was a detective in the Brooklyn North Homicide Division for the last 13 years of his tenure.

He investigated Mafia hits, was one of the detectives assigned to the infamous Son of Sam case and emerged as a decorated veteran with a 92 percent clearance rate on his cases.

“I had a lot of Mafia hits and they’re hard to investigate because nobody want to talk to you,” he said, adding, “I miss it. I’d go back tomorrow.”

After serial killer David Berkowitz’s car was identified, Crosby remembers being staked out near the Brooklyn Park where the car was parked one night when Berkowitz struck again, shooting a couple parked in a car a short distance away in one his signature attacks.

“We shot right over there. I almost had him a couple of times,” Crosby said.

Living with danger was a common condition for Crosby, who once learned that a gang member he had arrested had put out a contract on Crosby’s life while he was in prison.

“I’m living on borrowed time,” he said.

That thought recurs when he recalls the day near the end of his detective career when he was one of a cadre of cops surrounding Ralph’s Gun Shop in the early ‘80s when a group of four terrorists were holding 23 hostages inside after a botched attempted robbery.

“This went on for hours. The guy next to me got shot,” he recalled.

And Crosby was almost hit when the side door of the gun shop opened near the car he was concealed behind. A figure emerged with hands raised, saying “Don’t shoot, I’m a hostage.” But right behind that hostage was one of the would-be terrorists with a semiautomatic shotgun. Crosby ducked into the wheel well of the car he was standing behind as the shooter blew out the windows of the vehicle and then retreated back inside.

Ultimately, the heroic store owner led the hostages to safety through a hole he’d managed to cut in the plasterboard wall of the shop and the robbers were arrested. The incident was the basis of a thesis Crosby later wrote in the course of studying for a bachelors degree in criminal justice at John Jay College.

Crosby settled into a much less anxiety-ridden routine when he joined the state prosecutor’s office as a Medicaid fraud investigator shortly after retiring from the city police department in 1982. He directed a staff of 60 people as an assistant chief of the state Medicaid Fraud task force.

“We were among the pioneers of Medicaid fraud. It became a very involved job and we were very busy,” he said, noting that investigating the nefarious practices of nursing homes was a far cry from tracking down murderers.

But Crosby’s new role put him in harm’s way again on September 11, when he was standing in the plaza of the World Trade Center near his office when the first plane struck Tower One.

He immediately went to work, administering first aid to some of the victims who emerged from that building.

“I saw people falling and jumping,” he said.

When the first building collapsed, he found shelter in a nearby sub-basement, eventually emerging into the surreal scene unfolding on that infamous day.

“We were knee-high in debris when we got out,” he recalled.

He heard the same sinister whooshing noise he had heard when the first plane had struck moments later when the second plane hit the other tower. He remembered how the ground shuddered when the second building collapsed.

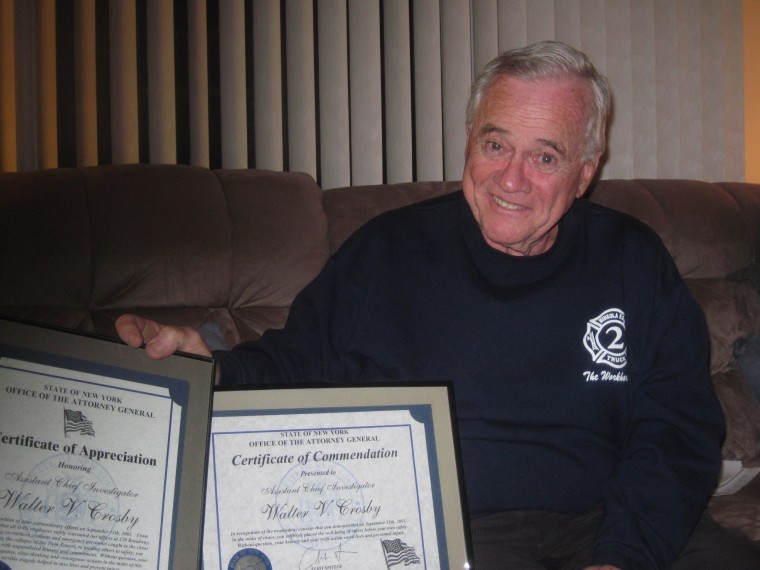

But mostly he remembers the incredible scenes of carnage and the heroism of the rescuers. He modestly downplays his own role, although he received a Certificate of Commendation from the state attorney general’s office for his actions that day.

“I was just in the right place at the right time. By the grace of God I wasn’t killed,” he said. “Anybody who says they’re not scared, they’re liars. Your training kicks in. But you want to get home to your family.”

A practicing Catholic, Crosby believes God had a purpose for him being in that place on that day. “No doubt about it,” he said.

He returned home to his wife, Grace, that day. And he’s thankful that he’s still able to enjoy the company of his four children, Jeanne, Michael, Thomas and Chris, and his three grandchildren, Lauren, Amanda and Michaela.

The people he helped on September 11 are doubtless grateful to him too, as are the people in his home community who have seen his service as a firefighter first-hand.

It was just a matter of being in the right place at the right time.