For Henry Diltz, the key to a successful photograph lies in how you frame the image.

The sentiment could be extended to his own life, Diltz said, moving from New York to Hawaii to become a folk musician and, once he was making music, picking up a camera and embarking on a legendary photography career that yielded more than 400 classic album covers taken mainly of his friends in Crosby, Stills & Nash and the Doors.

“It used to bother me to be so famous for all these past moments, but then someone said to me, ‘your photos help bring the past into the present,’ and I thought, oh okay,” said Diltz, 75, who now lives in North Hollywood,

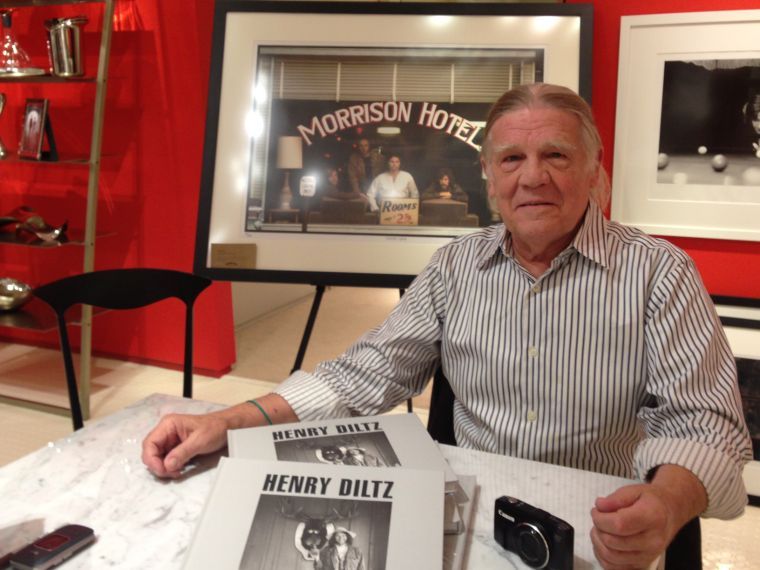

Diltz was back on Long Island on Saturday at the Americana Manhasset’s Mens Market at Hirshleifers, signing copies of his book “Unpainted Faces” and displaying his photography in the store’s new gallery in partnership with the Morrison Hotel Gallery, which he helped found with former record executive Peter Blachley and photographer Richard Horowitz.

“Music, wherever you are in life, is a huge part of our lives and our personal history, and history is a big part of it,” Diltz said. “Photography lets you see history through the eyes – lens, really – of the people who experienced it. It allows other people to share the vision of what the photographer saw and, depending on what he saw and how well he captured it, enlarges your own life, certainly.”

After Diltz’s father died in World War II, his mother remarried and relocated the family from Great Neck to Japan, but he later returned to Long Island and graduated from Great Neck High School in 1956.

While studying at the University of Maryland’s overseas branch in Germany, Diltz learned the children of slain soldiers could more easily sit for entrance examinations to United States military academies.

Diltz wrote a letter or two to the proper channels, sat for the exam and was accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point, but only stayed for a year.

But his heart was with music, Diltz said.

“I didn’t want to be an officer,” Diltz said. “I just really wanted to play the banjo.”

Diltz received a transfer to the University of Hawai‘i, where he studied psychology and began playing in folk bands. In 1962, Diltz formed the Modern Folk Quartet with Cyrus Faryar, Chip Douglas and Jerry Yester and moved to Laurel Canyon, California.

The band released two albums in the early 1960s, appeared in the Warner Bros. film “Palm Springs Weekend” and worked with producer Phil Spector in its last studio session in 1966 to record “This Could Be the Night,” which became the theme song for the concert film “The Big TNT Show.”

While on tour with the Modern Folk Quartet in 1966, Diltz bought a camera in a secondhand store in East Lansing, Mich., and began photographing the things he saw around him, most notably his friends – which included Steven Stills and David Crosby, whose own folk careers were beginning to blossom.

“And that was the start of my photography,” Diltz said. “I didn’t go to photography school. I didn’t know what I was doing. I just sort of figured it out from what it said on the photo box.”

Since Diltz’s first camera had been designed mainly for slideshow use, he hosted his friends for viewings of his work every few weeks.

“What was fun for me was to show them pictures I had taken days earlier of them,” Diltz said.

The first time he saw a slide of a photograph he took flicker on a wall, Diltz said “it blew my mind.”

“I thought, my God, this is magic, you know?” Diltz said.

“Something about the way the slide hits the wall all lit up like that. Digital [photography] just doesn’t do it the same way.”

Shortly thereafter, Diltz began receiving photography assignments, first to follow the Lovin’ Spoonful on their 1966 summer tour and the next year shooting the Monkees – specifically Davy Jones – for a host of newspapers and magazines. In the early 1970s, Diltz was called on for a similar assignment to photograph the Partridge Family’s star, David Cassidy.

During this time, Diltz also photographed a plethora of album covers, including Crosby, Stills & Nash’s 1969 self-titled debut and the Doors’ “Morrison Hotel” in 1970.

“I never once thought, boy someday this would be a piece of history,” Diltz said. “Never.”

Over the years, Diltz said he was approached numerous times by financiers wanting to open a gallery, refusing each time because he didn’t think they shared the same reverence for photography and music.

But after Diltz worked with Blachley on the documentary “Under the Covers” about the making of classic album covers from the late 1960s and early ’70s, and sold prints in the early 2000s with Horowitz, who was dealing photographs of John Lennon for the late Beatle’s estate, the trio – and their photos – wound up in New York City in search of a place to share their work.

Diltz said the group could not afford the Big Apple’s rent prices, nor could they even lease a space for a gallery, but they worked out an agreement to display their work for a weekend in a place up for lease in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood.

When the weekend was over, Diltz and Horowitz offered to leave the gallery open while the landlord continued searching for tenants.

After their initial space was leased, the early Morrison Hotel Gallery moved a few blocks away, and moved again when that space found a suitor.

“And so we stayed on Spring Street for a year, and then they leased the place, and then we stayed on Greene Street, and then they leased the place, and then finally we arrived on Prince street,” Diltz said.

The only thing missing was a name, Diltz said.

“The ‘Morrison Hotel’ cover was always in our front window, so we just figured, why not use the ‘Morrison Hotel’ name?” Diltz said. “I think it works really well for us. It says fine art music photography without screaming rock and roll at you, you know?”

Diltz today carries a camera in his pocket at all times, taking anywhere from 50-100 photographs a day, he said.

These days, Diltz makes appearances on behalf of the Morrison Hotel Gallery and answers many more requests for the use of his work than he said he’d ever imagined, and the photography – and the history it represents – lives on.

“People continue to be interested in it and the music lives on, and as long as the music lives on people will want to know what these people looked like,” Diltz said. “And as long as that happens, they’ll be interested in me.”