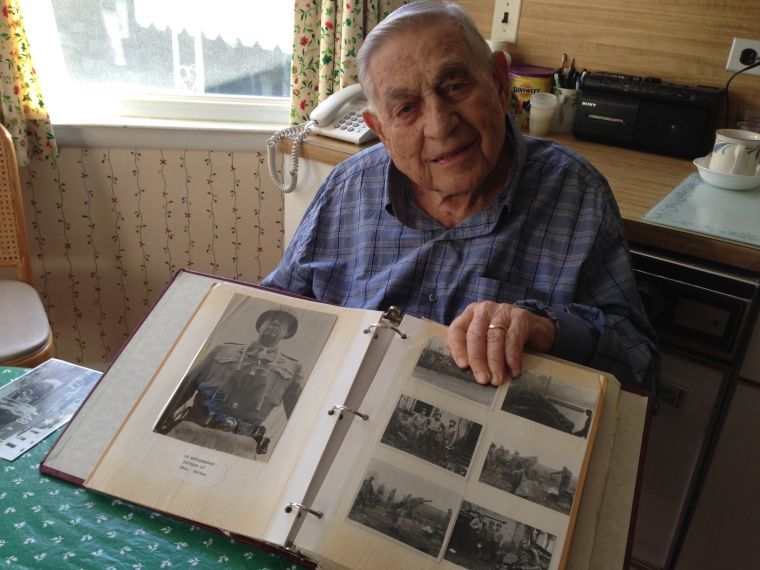

Plandome Heights resident Lawrence Kaplan keeps an autographed picture of General George S. Patton in a thick red binder filled with mementos from his service in World War II.

The binder’s pages are durable and laminated, containing photographs and documents from the time Kaplan was drafted into the military in 1942 to his discharge following the war’s conclusion.

Kaplan worked under Patton by way of Major General Robert W. Grow as a member of the 6th Armored Division, tasked with photographing and mapping enemy position so Air Force personnel could bomb the region and allow troops on the ground to advance.

“The job was to essentially save American lives,” said Kaplan in an interview from his Bay Driveway home, where he and his wife Jeanne have lived since 1977. “We didn’t want to be surprised by a guy coming out of the woods to intercept our guns and men. We made it safer for us to move forward.”

Kaplan, who celebrated his 98th birthday on Oct. 28, saw nine months of continuous battle and earned five battle stars at Normandy, Northern France, the Rhineland, the Bulge and Central Europe. He was also part of the Allied forces that helped liberate the Buchenwald Concentration Camp in 1945.

For his accomplishments on the battlefield, Kaplan received the New York State Conspicuous Service award, a citation from the Republic of France for “Liberation From German Domination,” and was profiled by Who’s Who in America.

“I made some great friends in the military and I think I contributed a lot and did what I was able to do to help our American forces,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan was born into a Bronx household that was so poor there wasn’t enough hot water to aid in his birthing process, and three years later the family moved to Coney Island so Kaplan’s father could make money as a tailor.

Kaplan attended P.S. 188 in Brooklyn and then New Utrecht High School for a year before moving on to Abraham Lincoln High School when it first opened in 1929. He graduated in 1933.

Kaplan was drafted in 1942 and sent to Lafayette College in Easton, Pa., where the Army stockpiled the best and brightest young men who might someday make candidates for officer training and military intelligence.

Among Kaplan’s classmates at Lafayette were former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, former U.S. Senator Frank Church [D-Idaho] and former West Virginia Governor Arch Moore.

“I came to understand the selections they made were of the top-notch individuals with the highest IQs and grades,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan studied Spanish language, culture and history for six months and was then sent to Fort Ritchie in Maryland for military intelligence training.

There, Kaplan said, he learned how to use stereophonic lenses to photograph troop movements and identify bases, tanks, weapons and ammunition.

“The interesting thing about military intelligence is that it was never about rank. I was in classes with colonels and generals and learning with the same teachers,” Kaplan said. “I turned down officer training school. It wasn’t important to me. If I liked what I was doing, what did rank matter? I did my job and I was happy with that.”

In June of 1944, Kaplan continued his military intelligence training in Britain, which included learning to drive a car.

Kaplan’s testing involved driving a jeep up a hill, stopping halfway and then continuing to the top of the hill.

Kaplan flunked the test and went back to the barracks, where he was met by a sergeant who told him not to worry about the failed exam.

“It’s very easy to make an ‘F’ into a ‘P’,” Kaplan said the sergeant told him. “All you have to do is connect the two lines, he told me, and that’s how I got my license.”

Kaplan later had to learn to drive every vehicle in the military, including tanks.

To test his driving skills, Kaplan had to drive a 2.5-ton truck through Kinghtsbridge, a heavily-populated downtown area.

“I took the test, got through traffic and did it on the wrong side of the street,” Kaplan said.

Shortly after Kaplan joined the 6th Armored Division at Batsford, England, the division made a 10-day, 250-mile trip on the Brittany Peninsula to help surround the German base at Brest, capturing 5,000 Nazis along the way while suffering light casualties.

“The entire campaign was a complicated, leap-frogging affair,” according to a Stars and Stripes newspaper account from that time. “Gen. Grow’s men sometimes surged forward so rapidly that they found themselves operating beyond areas covered by the maps in hand.”

While in Europe, Kaplan said he got to know Patton when the general would come to division headquarters for meetings.

By this point in the war, Patton had already amassed his rock star celebrity, and around carried autographed photographs of himself to give to troops.

One of the photographs went to Kaplan.

“I got to know him a little bit, sure,” Kaplan said. “I didn’t talk to him too much, he had other things to get to rather than talk to me, but we were all in there together. It doesn’t matter whether you’re at division headquarters or what when planes are firing at you from overhead.”

Kaplan said Patton assigned the 6th Armored Division to liberate the 101st Airborne Division, which had been surrounded by the Germans at Bastogne, in Belgium.

“The Germans thought if they could knock out the weak areas of the American Army, they could win the war,” Kaplan said.

The 6th Armored Division traveled overnight on Christmas Eve of 1945 through one of the worst Belgian winters in history.

“The roads were full of snow, and we never slept indoors unless we got very lucky,” Kaplan said. “At one point in our travels, we saw a house that looked warm and lit-up from the outside. We knocked on the door and how lucky were we that it was a nunnery. They welcomed us inside and gave us their beds, and they took heated bricks and wrapped them in blankets and put them next to our feet to warm our frozen toes.”

The 6th Armored Division successfully liberated the 101st Airborne, helping reverse the fortunes of the Battle of the Bulge.

“Whereas it looked as though it was going to be a great victory for the Germans, it turned out to be a great victory for the Americans,” Kaplan said.

After the Axis powers surrendered to end the fighting in Europe, Kaplan turned down an opportunity to join the fighting in the Pacific.

“The fighting in Europe exhausted me, absolutely exhausted me,” Kaplan said. “I just wanted to get back to the States and start my life, you know?”

Kaplan was sent back to America on a troop ship and said he was in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean when the crew received word that the Allied forces had dropped two atomic bombs on Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“That’s how I found out the war was over,” Kaplan said. “I was halfway across the Atlantic.”

Kaplan was stationed at Fort Bragg in North Carolina until his discharge on Nov. 18, 1945.

When he returned to New York, Kaplan began taking Ph.D. classes in economics at Columbia University and teaching at any school that would pay him for a day’s work.

But Kaplan was eager to settle down, remembering long nights in Europe unsure he’d survive the fighting, “and then the world would have never have known that there was a Larry Kaplan from Brooklyn,” he said.

“In my mind, I had to find a young woman who I could love and raise a family with and have some progeny,” Kaplan said.

While taking the bus one morning to a teaching job at Lafayette High School in Brooklyn, Kaplan saw a young woman holding a box filled with leftover wedding cake.

The woman got off the bus with him at Lafayette, and Kaplan was surprised to find she not only taught at the school, but also shared his lunch period.

Despite his five battle stars and autographed photograph of Patton, Kaplan said he had another teacher approach the woman and tell her he’d like to get to know her and take her to the movies.

That young teacher was Jeanne.

“I knew she was the one for me,” Kaplan said. “I knew she was the one I was going to marry.”

The two began dating and Kaplan landed a job with the federal government.

Kaplan said he told Jeanne he didn’t want to go to Washington, D.C. alone. Jean told him she had grown tired of writing so many letters to boys overseas during the war.

Kaplan proposed, just seven weeks after the couple met. Jeanne said yes. They’ve been together ever since.

“Jeanne started that binder a little while after we got married,” Kaplan said.

When the couple’s first child, Harriet, was born, Kaplan’s father fell ill and his mother asked they move back to New York to help the family.

Kaplan began teaching economics at Baruch College and later was the first to chair the John Jay College of Criminal Justice economics department from 1965-85, when he was required by law to retire from being a full-time professor.

“My plan all along was to become a professor,” Kaplan said. “That’s really all I set out to do.”

The Kaplans had two other children, a son Sanford and a daughter Marcia. The Kaplans now have seven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren