By Karen Rubin, Travel Features Syndicate, goingplacesfarandnear.com

From its founding in the 1930s to the end of weekly publication in the 1970s, LIFE Magazine elevated and showcased photojournalism. Instead of just being the accoutrement to reporting, the photos were the story, or as Henry R. Luce saw it, the photojournalist as essayist.

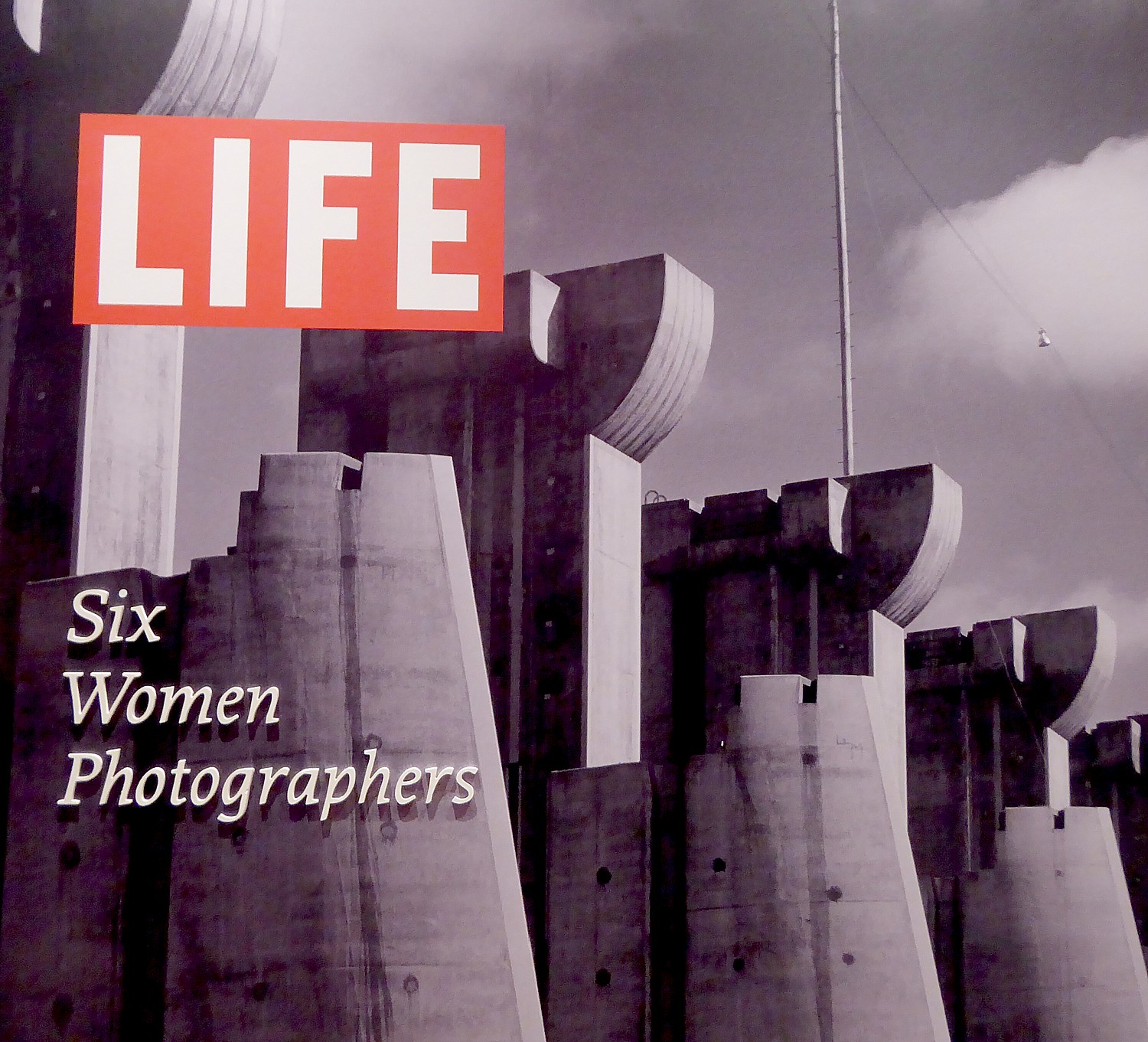

During that time, only six out of 101 full-time LIFE photographers were women. Now, for the first time, these women – who contributed so much to the evolution of photojournalism as well as the cultural and societal trends they spotlighted – are featured in their own exhibit, LIFE: Six Women Photographers, at the New-York Historical Society through Oct. 6.

“For the editors of LIFE—the first magazine to tell stories with photographs rather than text—the camera was not merely a reporter, but also a potent commentator with the power to frame news and events for a popular audience. For decades, Americans saw the world through the lens of the magazine’s photographers. Between the late 1930s and the early 1970s, LIFE magazine retained only six women photographers as full-time staff or on a semi-permanent basis. LIFE: Six Women Photographers showcases the work of some of those women and how their work contributed to LIFE’s pursuit of American identity through photojournalism,” the curators write. The exhibition features more than 70 images showcasing the extraordinary work created by Margaret Bourke-White, Hansel Mieth, Marie Hansen, Martha Holmes, Nina Leen, and Lisa Larsen.

How were these women part of a larger editorial vision? What topics did they cover, and how did their work reflect—and sometimes expand—the mission of the magazine? The exhibit reveals these photographers’ important role in creating modern photojournalism and defining what LIFE editor-in-chief Henry Luce called the “American Century.” The level of influence that LIFE Magazine wielded was considerable – at its height, one out of every three Americans read the magazine each month.

We learn that of the six, three were immigrants, including two who fled Fascist Europe. In all, they produced 3,000 stories, 325,000 images that curator Sarah Gordon, curatorial scholar in women’s history at NYHS’ Center for Women’s History, and Marilyn Satin Kushner, curator and head of the Department of Prints, Photographs and Architectural Collections, combed through to select out the 70 images featured in the exhibit. The exhibit, interestingly, highlights not only the photos that were selected for publication, but photos out of the series that were not as well as the contact sheets. There are also displays with the magazine opened to the page, and notes from the photographers that give extraordinary insight into their perspective, as well as the editors’.

Asked how the six featured stories were selected out of the photographers’ 3,000, Kushner reflects, “We thought about what we wanted to show and say – that kept me up at night, how to tie as a thread. The first thought was to show a woman’s point of view, but then we don’t know how a man would have treated the same subject. What the women did was illustrate Luce’s idea, that the photos [depict] the American story.”

Yet, except for Margaret Bourke-White’s famous series on the Fort Peck Dam – illustrative of her talent to show Industrial America and technological progress – the photo essays selected for this exhibit predominantly show women and women’s issues – wrestling with their place in society after World War II’s independence, the WACS. And even when there is a story, like the Dam, Bourke-White and others showed a great sensitivity to how ordinary people – families – lived. Bourke-White chose to show shantytowns that developed around the dam and what the Saturday night dance hall was like.

Her telegram to her editor reads, “Swell subjects especially shanty towns. Getting good nightlife. Nobody camera shy except ladies of evening but hope conquer them also…. May I give one picture FortPeck Publishing booklet for local sale. Would help repay their many courtesies. Could choose pattern picture we probably wouldn’t use anyway.”

How did they get their assignments? “Sometimes the women wrote and asked for an assignment, but usually were told to ‘do that’” Kushner tells me. Luce wanted LIFE Magazine to reflect the American Century, and while Bourke-White documented steel mills and dams – America’s technology and industrial achievements – she also depicted new towns in the middle of nowhere, “FDR’s New Wild West.”

Standing in front of one of the most controversial and substantial photos in the exhibition – Martha Holmes’ 1949 image of singer Billy Eckstine being embraced by a white female fan, surrounded by other gleeful white teenagers – I meet Holmes’ daughter, Anne Holmes Waxman, and granddaughter of the photographer, Martha Holmes., Eva Koshel Castleton.

“My mother came on when a lot of men were in the war,” Waxman said. Born in Louisville, Ky., she was working as a photographer at the Courier-Journal when LIFE Magazine came to recruit her to come to New York. “She was shaking in her boots, just 24 years old. She never went back.”

The exhibit shows the contact sheet with other images of multiracial crowds waiting for tickets and autographs, but the editors chose to publish the more controversial image. They were so concerned that they sought permission from Luce, who agreed with Holmes that the photograph reflected social progress and was appropriate for the story. “Holmes felt the photo was one of her best, claiming ‘it told just what the world should be like.’ The magazine, however, received vicious letters in response and the fallout adversely affected Eckstine’s career,” the notes read.

In the weekly report of letters received for the April 24, 1949 issue, “Fifty-nine readers are very much upset. ‘That picture of Billy Eckstine with a white girl clinging to him after a performance just turns my stomach. Why a teen-age white girl conducts herself in this manner over a Negro crooner is beyond me. Juvenile delinquency is bad enough in our own race without mixing it up with another.” “The most nauseating picture of the year.” “That picture qualifies as the most indecent picture ever published by LIFE.” “ That picture should have appeared in Pravda Your publication of it leads me to believe that Mr. Chambers was not the only Communist on your staff.” Eight readers cancelled their subscriptions, but nine praised the feature.

I ask her daughter Anne Waxman whether her mother got or lost certain assignments because of being a woman. She said the only assignment her mother turned down was when he was 8 ½ months pregnant with her in 1956 and had to refuse an assignment to photograph Elvis Presley. “It was the one job she couldn’t take.” But she is renowned for her photos of artist Jackson Pollack and the House on UnAmerican Activities hearings.

A very interesting series, “The American Woman’s dilemma” by Nina Leen, that was published in the July 16, 1947 issue, danced around the issue of “how are you going to get them back on the farm, after they’ve seen Par-ee” – in this case, women who worked traditionally male jobs and had independence during the war now being shoved back into housework and child-rearing rather than pursue a career. “The essay also reflected cultural anxieties about a ‘return to normalcy’ after the Depression and war. LIFE assumed that all women desired marriage and children but voiced concern that a woman’s time was so stretched, she did not have time to pursue her husband’s interests.

“The article barely acknowledged that many women had no choice but to find work. It did recognize women’s struggles with child care but disparaged separation as creating insecure children.” Only one of Leen’s photos of an unmarried woman made the cut. “This article represented a clear attempt at setting out women’s choices in the post-war era of societal realignment.”

What I notice in the spread of the article displayed is that it is opposite an ad for Singer sewing machines; LIFE Magazine clearly had an investment in women as homemakers, wanting the latest appliances.

Similarly, that controversial Eckstine spread by Holmes? It is featured in the display with the ad for new Coty eye cosmetics: “Eyes of natural glamour. Newest style in beauty.”

Marie Hansen’s series “The WAACs” (Sept. 7, 1942) helped America accept the idea of women in uniform.

Hansel Mieth is represented by her feature on “International Ladies’ Garment Workers: How a Great Union Works Inside and Out” (Aug. 1, 1938). She worked as a migrant worker in California when she first immigrated to the United States from Germany and photographed fellow migrant workers in San Francisco, the city’s neighborhoods and cultural enclaves before LIFE hired her in 1937, publishing her socially engaged photo essays over the next seven years.

Luce wasn’t being progressive in hiring women photographers for their point of view. He was realizing that women were the market for advertisers. And they were used to socialize women back to their pre-World War II prescribed roles.

I am left to wonder to what extent were the projects reshaped by a woman’s perspective, or how much the women photographers were directed to focus on “women’s subjects.” Even Lisa Larsen’s feature, “Tito as Soviet Hero, How Times Have Changed!” (from June 25, 1956) featured as a spread, “Wives Materialize to Greet a Visitor.” I wonder to what extent, as the women photographers cemented their footing, they were able to take a stance instead of being the instruments. We would have to see many more examples of the photographers’ assignments to make that appraisal, and hope these topics will be revealed in future exhibits at the NYHS Women’s Center.

The exhibit is curated by Sarah Gordon, curatorial scholar in women’s history, Center for Women’s History, and Marilyn Satin Kushner, curator and head, Department of Prints, Photographs and Architectural Collections; with Erin Levitsky, Ryerson University; and William J. Simmons, Andrew Mellon Foundation Pre-Doctoral Fellow, Center for Women’s History.

NYHS brilliantly uses its space to maximize an immersion into Women’s History. Just outside the Women Photographers of LIFE Magazine exhibit is Women’s Voices, a multimedia digital installation where visitors can discover the hidden connections among exceptional and unknown women who left their mark on New York and the nation, even going back to Colonial America. Featuring interviews, profiles, and biographies, Women’s Voices unfolds across nine oversized touch screens to tell the story of activists, scientists, performers, athletic champions, social change advocates, writers, and educators through video, audio, music, text, and images.

There are also displays about the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, Women’s Activism and tennis great Billie Jean King. And in the middle of the floor is a most sensational gallery devoted to Tiffany, which includes a fascinating display about Clara Driscoll, who headed the Women’s Glass Cutting Department of some 45 to 55 young women (mainly 16- and 17-year-olds who would work until they went off to be engaged). And who until this exhibit was unheralded for her role in creating many of Tiffany’s iconic designs.

New-York Historical Society, 170 Central Park West (77th Street), New York, NY 10024, 212-873-3400, nyhistory.org.

_____________________________

© 2019 Travel Features Syndicate, a division of Workstyles, Inc. All rights reserved. Visit goingplacesfarandnear.com, www.huffingtonpost.com/author/karen-rubin, and travelwritersmagazine.com/TravelFeaturesSyndicate/. Blogging at goingplacesnearandfar.wordpress.com and moralcompasstravel.info. Send comments or questions to FamTravLtr@aol.com. Tweet @TravelFeatures. ‘Like’ us at facebook.com/NewsPhotoFeatures