Bt Ross Lumpkin

World-renowned architect I.M. Pei died May 15 at the age of 102. Never afraid of controversy, his best-known buildings, such as a glass and metal pyramid at the Louvre Museum in Paris, an angular addition to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the iconic Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, are innovative examples of modern architecture.

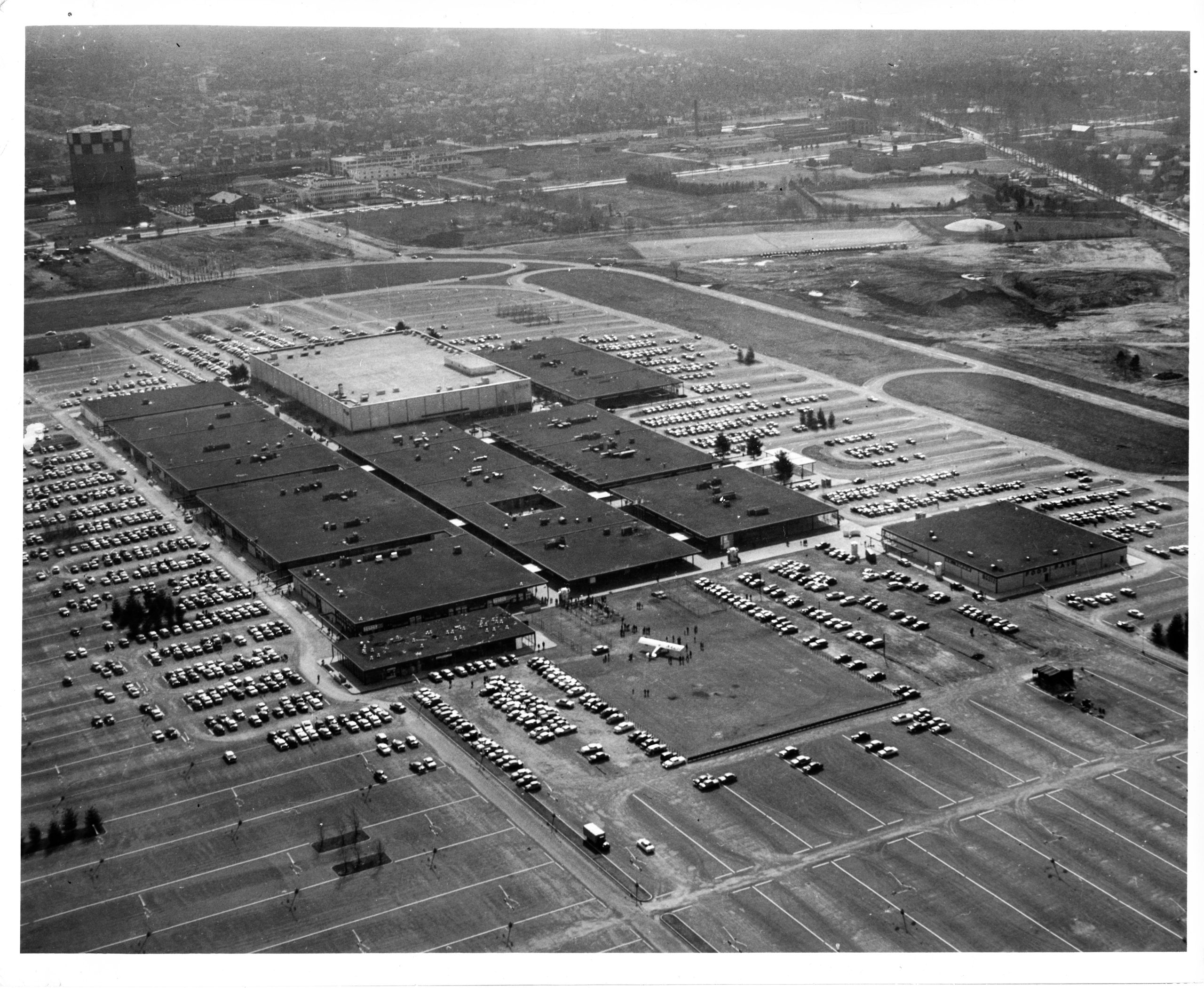

So, it is surprising that his first major project, completed in 1956, was the Roosevelt Field Mall in central suburban Nassau County. Surprising, first, because his original design has been renovated beyond recognition, and second, because shopping malls and high-minded architects seem to make strange bedfellows. One wonders how it came to pass that an architect like Pei would be involved in a blatantly commercial project.

It took a developer like William Zeckendorf, who had a deserved reputation as a patron of architecture (think United Nations) to convince him that this was not going to be just a shopping district. He envisioned a center of commerce in the spirit of an Italian piazza, a gathering place for the community, which would, thanks to the new network of highways that Robert Moses was building, be accessible to a million residents within a 10-mile range – the largest mall in the world.

Pei had established himself as an exceptional talent at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and came recommended as the up-and-coming modern architect by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. Zeckendorf wooed him with artistic independence, financial support, and the opportunity to design an alternative to the decaying downtowns overwhelmed by rapid post-war growth on Long Island.

The modern open-air mall of 1956 exists only in the collective memories of those who were lucky enough to go there before it was enclosed in 1964. What follows are some of those memories that were posted on the Long Island History blog. “Orange and white lamps in the parking lot – sort of like basketballs…the octagonal stone pavers, cobblestone surfaces…a trolley like the ones in Disney that would travel up one side of the mall and down the other…the open plaza, the kiosks, pretzels – so much fun.”

Some of those memories remind us as well of a very different time. “Sorority girls in costumes selling squares of toilet paper as a part of their hazing…the large water fountains where someone would occasionally throw laundry detergent…my dad would drive me over to the ice-skating rink, give me money for hot chocolate, and come back a couple of hours later.”

Long Islanders aren’t so sentimental when our thoughts turn to traffic. “The mid-century car culture was a big mistake.” Indeed, “Big Bill” Zeckendorf had made a deal with “Power Broker” Robert Moses to insure the success of his project. In exchange for 48 acres of land donated to the Jones Beach Parkway Authority, he got a cloverleaf interchange on the Meadowbrook Parkway that would feed traffic directly into his mall.

Guiding heavy traffic from parkway to parking lot and pedestrians from cars to the shopping area was a new problem for planners. Pei understood that smooth traffic flow would be critical to the success of the project and devoted significant time to finding a solution.

He settled on a ring road surrounding the parking lot that, in turn, surrounded the shopping area. Traffic coming from the Meadowbrook cloverleaf could go north or south on an interchange at the ring road, and then enter the parking lot from an exit that would place them in the vicinity of their destination. The ring road concept has come to be used extensively ever since to ease congestion, most notably in beltways around major urban areas.

The hangars and the runways of the Roosevelt Field airport where Lindberg took off for Paris in 1927 had long been deserted and consequently become rundown by the time Zeckendorf arrived on the scene. Whether he was motivated by respect for history or a keen marketing sense isn’t known, but either way he seemed to appreciate those hallowed grounds. At the opening ceremony in 1956, he had a few generals along with 200 cadets from 22 countries on hand to mark the occasion. One year later, when the film “The Spirit of St Louis” was released on the 40th anniversary of Lindberg’s historic flight, he placed a replica plane (visible in the photograph) outside the theater in the parking lot.

I had heard that there were still some octagonal pavers and a historic plaque outside Macy’s and went over there to see what I could find. Sadly, I may have just missed the pavers for they were in the midst of another renovation. No plaques anywhere, until my last desperate stop in the basement of Macy’s where there was a plaque in temporary storage, in an office also known as Lost and Found.

Ross Lumpkin is a trustee at the Cow Neck Peninsula Historical Society, www.cowneck.org.