For Dr. Pamela Gallagher, the life of a plastic surgeon is not exactly the glitz and glam of celebrity butt injections and facelifts that people may be used to seeing on television.

Sitting down in her practice at Long Island Plastic Surgery in Mineola, Gallagher scrolls through a photo album full of before and after images of children, most often babies, suffering from cleft lip and palate birth defects.

The ability to change a child’s life, from one of possible ridicule for their appearance to a more normal appearance, is a reward in itself, Gallagher said.

Gallagher works on children with cleft birth defects to not only avoid the physical and medical complications that may come later in life if left untreated, but to give children a healthy sense of pride and improved self-esteem, like any other person who comes in for plastic surgery.

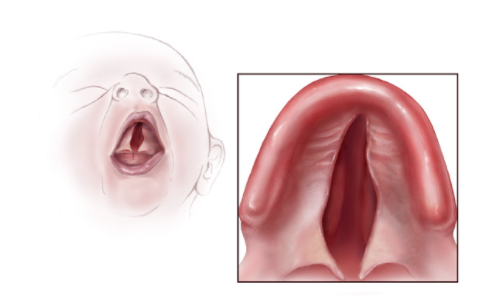

Cleft lip and cleft palate are birth defects that occur when a baby’s lip or mouth do not form properly during pregnancy. A cleft lip develops during pregnancy, when the tissue that makes up the lip does not join completely before birth. This results in an opening in the upper lip, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website.

Those with a cleft lip may also have a cleft palate, which occurs if the tissue that makes up the roof of the mouth does not join together completely during pregnancy.

According to the CDC, more than 4,400 babies are born each year with at least a cleft lip, and possibly a cleft palate.

The work, though time-consuming and highly involved, is often done on a pro bono basis or for very little monetary compensation, sometimes for children whose citizenship status is unclear.

“If you need the care, you get taken care of,” Gallagher said, referring to a motto by the New York Center for Orthognathic and Maxillofacial Surgery. For a long time, the center was one of the few supporters of Gallagher’s Cleft Palate Centers, dedicated to the work she does with children.

Delicate planning and revolutionary work in the field of plastic surgery both play a role in Gallagher’s cleft work. Baby cartilage is, to some degree, pliable, and can be molded and reconstructed to eliminate the clefts, she said.

Gallagher said that often she will work with professionals from different medical specialties to tackle problems, which are unique on a case-to-case basis.

“You’re not stuck in a rut, you can be inventive,” Gallagher said.

Gallagher has began using stem cell technology in some patients, to try and mitigate the scarring that sometimes occurs even after a successful cleft surgery. Fat cells are reduced to a nano-fat borderline stem cell composition and injected into the scars. Gallagher is currently waiting from results from one particular case, but is hopeful about the results.

Being able to help children with something like their self-esteem through surgery, for Gallagher, provides a type of instant gratification that is hard to achieve elsewhere, she said.

Born in Brooklyn and raised on Long Island, Gallagher knew since she was a child that she wanted to help people and be a doctor. Though criticized and subject to the view in the 1950s that women could not work in science and technology fields, Gallagher persisted.

She eventually met her husband, John Gallagher, and they attended medical school at the University of Chicago in a period when it was only just becoming acceptable for couples to study concurrently. John went on to work as vascular surgeon for decades, achieving ground-breaking work, Pamela Gallagher said.

Today, Gallagher is continuing to push the boundaries of plastic surgery, using new technology, like EMSculpt, a machine that builds muscle and burns fat, and noninvasive methods, like light and sound waves, to achieve results.

A pervasive problem Gallagher saw in her personal life and directly related to her work was the selective ageism that she says is apparent in society.

Despite her father being in great shape at the age of 102, Gallagher realized physicians, and some people, were quick to dismiss his concerns about a recent health issue as “just being at that age.” Gallagher connected this assumption about his problem, which was later found to be diagnosable, and the consultations and procedures she does every day.

The stigma surrounding plastic surgery, that it is the result of vanity and selfishness, is not what Gallagher sees every day.

She sees people who, for whatever reason, have aged or seen their appearances change over time. They wish to look more like their true selves than what appears in their reflection, she said. And again, she added, she receives a sense of gratification from helping people feel more comfortable in their own skin.

“It’s about peace of mind,” Gallagher said.