Stepping inside the Kupferberg Holocaust Center, a long corridor of documents, maps and photos detail the life of Benzion Persecki – later known as Ben Peres.

At the center of it is a rare artifact: a jacket kept from his time in the Dachau concentration camp in Germany.

It is an especially rare find.

Whereas many Holocaust survivors might have chosen to discard or burn any memories of the tragedy, the garment remained in his closet his entire life – and 37 years after, when it was discovered in an estate sale by antique clothing collector Jillian Eisman in 2015.

Eisman, whose grandfather was drafted into the Soviet Army in World War II and whose brother died in the September 11 terror attacks, immediately recognized it as an object of pain, suffering and resilience.

“I think others will feel very strongly when they see the jacket and they see the rust-colored stains and the dirt and the documents that go along with it, and that this was somebody’s life,” Eisman said in an interview with the Kupferberg Holocaust Center, which is located on the campus of Queensborough Community College in Bayside. “This is a lot of lives, and we can change things.”

Peres’ family never knew of the jacket’s existence.

But when they were reached out to, they responded by helping develop the exhibit and donating boxes of documents.

“They were surprised that their father had kept it because he never seemed to someone lost in the past or guided by his past,” said Dan Leshem, the co-curator of the Jacket from Dachau exhibit. “He seemed very loving and warmhearted and gregarious rather than traumatized and backwards-looking.”

These documents, photos and undeveloped film chronicled Peres’ battle for reparations from the German government in wake of the Holocaust, his time in a displaced persons camp, and how he survived the Holocaust.

But it also showcased a kind, resilient man searching for identity, justice and home.

They are also complemented by historical context, detailing Jewish culture in pre-war Lithuania, widespread discrimination and violence within Nazi Europe, life in the Ghettos and just how many people died in the Holocaust.

Lithuania, where Peres grew up, saw 85 percent of its Jewish population murdered.

Sam Widsawsky served as a proxy for Peres when it came to explaining life in the Dachau and Kaufering labor camps. There they worked grueling hours creating rockets and munitions, while enduring malnutrition, beatings and frequent death marches.

“His story is definitely one a sort of a miracle. He continued to fight and fight and he didn’t let that stop him,” said Abigail Jalle, an intern who helped assemble the exhibit. Even his mother proved to be a fighter, she added.

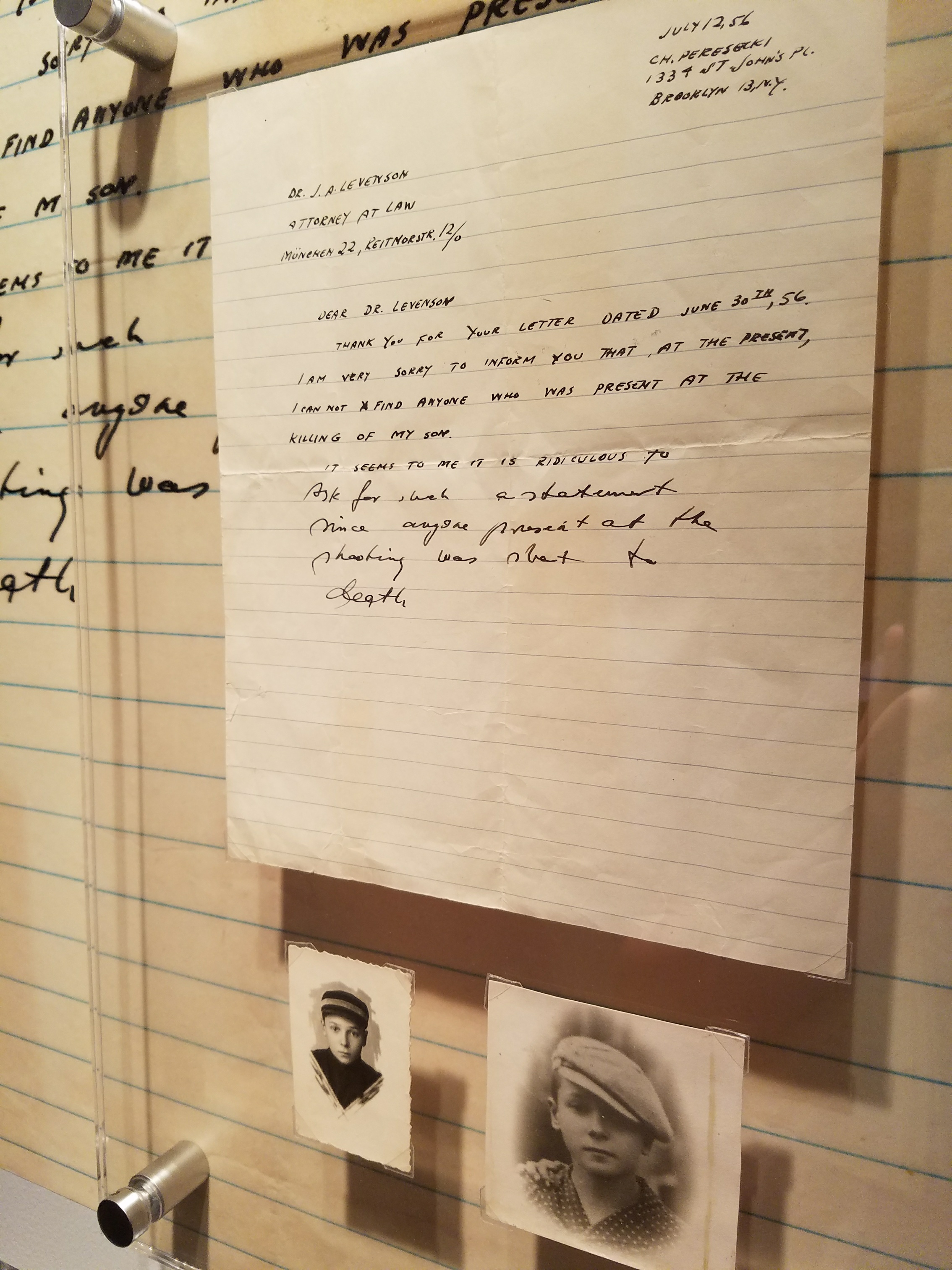

One piece of the exhibit that stands out particularly to Leshem is a letter Peres’ mother wrote to a lawyer in seeking reparations for her oldest son Levi-Ichak, 15 years after his death in July 11, 1941. Her writing begins neat and tight. But come the second paragraph, it morphs into a chaotic cursive that goes off the lines.

“What you see in this document, which is really remarkable because normally we think of video being able to do this but not two-dimensional documents, is that you see the passage of time and you see an emotional transformation that takes place inside of her,” Lesham explained.

The exhibit aims to end more positively. A video of Peres’ wedding shows beaming patrons, mostly Holocaust survivors.

“I think for students, it’s very important to end on this note of thinking of victims of these atrocities not only as victims, but as people who were resilient and were able to continue living and to overcome,” Leshem said.

Just beyond this video, multi-colored post-it notes from reflecting students drape a lobby wall. While most answers were in English, there were others in a few different languages. Leshem speculated that the people either wanted their communication with Peres to be secret, or that there were feelings only their main language could convey.

“It’s amazing to see how much the students have grown attached to him,” Jalle said, noting that she herself saw him as a friend.

In conjunction with the exhibit is a fully immersive online one, set to debut within the next few weeks offering many ways to navigate. In this way, it will remain even after the exhibit departs at summer’s end.

The website hopes to cater to multiple learning styles, so that any type of professor can use it. It also aims to stir a global conversation, with questions from the exhibit being connected to Facebook.

“It is by far the most ambitious exhibit the center has ever tried,” Leshem said.

The Jacket from Dachau exhibit is located at the Queensborough Community College at 222-05 56th Ave, Bayside, NY 11364.