Harvey Kaylie, a Kings Point resident since 2003 who rose from poverty to found Mini-Circuits Inc. and become a major philanthropist for causes throughout Great Neck and the world, died last Wednesday. He was 80 years old.

Friends and colleagues recalled Kaylie as a man with a sharp mind but generous nature, always trying to bring out the best in people, whether it was through so-called “challenge grants” or personal conversations.

“He was a combo of a brilliant mind – he was always sharp, always focused, always giving ideas no matter what the topic – and he also had a very big heart,” Alan Steinberg, a vice president for finance at Yeshiva Har Torah and Great Neck resident, said in an interview.

And despite “his reputation as a major philanthropist and major man in industry, he was very approachable,” Steinberg added.

The Kaylies, through the Harvey and Gloria Kaylie Foundation, have given millions of dollars each year since the year 2000 to a variety of religious and educational institutions, according to tax filings – between 2011 and 2016 alone, the Kaylies donated more than $30 million.

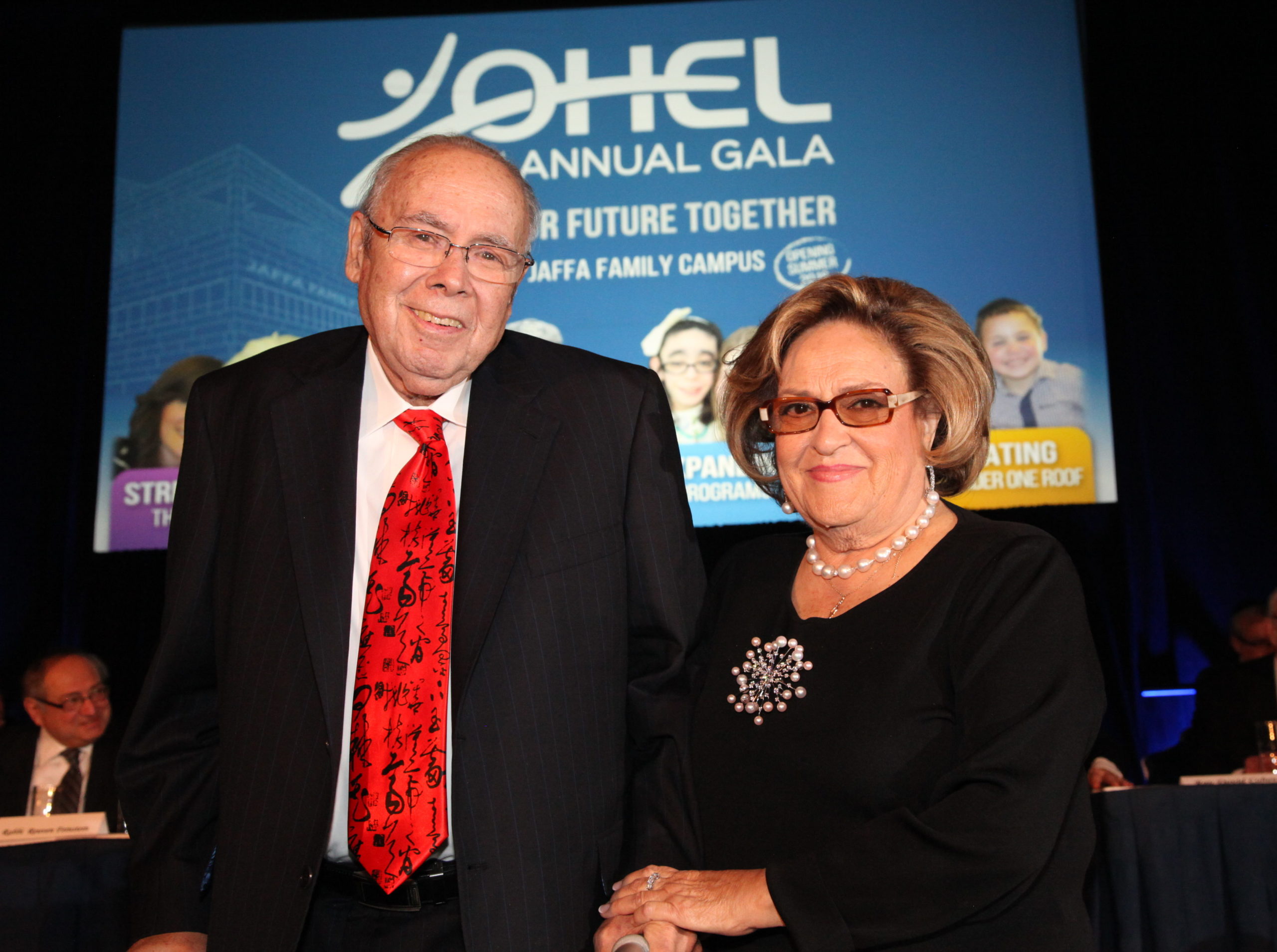

Among some of the biggest recipients are the City College of New York, where Kaylie graduated in 1960, the Brooklyn-based OHEL Children’s Home & Family Service, Yeshiva University, Weil Cornell Medical College and American Friends of United Hazalah.

The Kaylies also donated to local institutions like Yeshiva Har Torah in Little Neck, Great Neck Synagogue, Chabad of Great Neck and the Gold Coast Arts Center in Great Neck Plaza.

Regina Gil, the executive director of the Gold Coast Arts Center, recalled when Kaylie helped introduce the first challenge grant for the institution, which he believed was pivotal to downtown revitalization.

“He made you the best person you could be,” Gil said, describing him as “one of those brilliant engineering minds” and someone who never said “no” to a charity. “He wasn’t just giving money away – he made you earn it.”

David Mandel, the head of OHEL Children’s Home and Family Services, said his group’s relationship with the Kaylies began 20 years ago with them looking for somewhere to donate Hanukkah gifts.

It would eventually develop to the Kaylies being a key supporter of a camp that brings together “typical children” and children with special needs and empowers them, which Mandel and Steinberg both said was one of Harvey Kaylie’s favorite accomplishments.

“When we presented the concept to Harvey, he immediately thought that it was not only a good way to break down stigmas, but his words were, ‘this teaches kids to understand people who are different so when they grow up, they will not have biases that adults have,’” Mandel said.

Rabbi Dale Polokoff of the Great Neck Synagogue said that from the very first conversation he had with Kaylie, he knew he was speaking with someone “who was clearly not your usual congregant.”

One of the ways Kaylie supported the synagogue was by backing the adult education program. He took a “very active role” in it, Polokoff said, monitoring the program and suggesting ideas for the brochure to make it more attractive.

But his support went well beyond financial, Polokoff noted, with Kaylie freely giving advice and his time.

“I think that the Jewish community and the general community has lost a tremendous friend,” Polokoff said, adding that “nothing made Harvey Kaylie happier than to see other people succeed.”

Harvey Kaylie was born on Sept. 20, 1937, in Brooklyn, and raised by his single mother, Tess Kaylie, along with his younger brothers, Jerry and Marvin.

In his book “From Zeidie to Zeidie: Memories and Stories from the Life of Harvey Kaylie,” Kaylie said his mother was a “truly special person” who had been thrown more than her “fair share of difficulties.” But she carried on without complaint, he said, and carried a deep faith in the goodness of others.

“As the eldest in our family, I felt the need to help my mother as much as possible, and to act as a sort of protector for my younger brothers,” he wrote. “It never occurred to me that I was just a child myself, still attending school and playing games like others my age. I had an entrepreneurial urge to make money and support my family.”

Kaylie also recalled how his mother would patch the boys’ shoes with paper, walk miles to save pennies on bus fares and stretch meals to last, as well as times when he took on odd jobs and worked in a furniture store with family members.

“She taught him that values are more important than valuables,” Steinberg, Kaylie’s friend for several years, said. “He didn’t buy a lot of toys and expensive things: he always thought values are more important than valuables.”

“He once told me he was so poor he could barely afford a pair of shoes,” Gil recalled in a separate interview.

Kaylie went on to graduate from junior high school at 12 years old and high school at 15, and attend the City College of New York. He at times had to leave college because of family responsibilities, Kaylie said in his book, but he graduated with a degree in electrical engineering in 1960 and later get a master’s degree in electronic engineering from New York University.

Kaylie worked as an electronics manager for Airborne Instruments Laboratory and as an engineer at Dumont, Phillips and ITT before founding Mini-Circuits, which designs, manufactures and distributes small parts used in signal processing, in 1969.

These components found their way into everything from cellphones and computers to transmitters, medical equipment and other items.

“When Harvey took a leap of faith and left his job to strike out on his own, I supported him entirely,” his wife, Gloria, whom he married in 1961, wrote in “Zeidie to Zeidie.”

Speaking more generally, Gloria wrote that her husband had something few others had: heart and smarts.

“Not only is he very smart, but he also has a very accepting and good heart, and I knew we were a perfect match – the best partner I could imagine in my lifelong focus on positive energy,” Gloria Kaylie said.

In addition to his wife, Harvey Kaylie is survived by his children, Roberta, Alicia and Daniel, and his grandchildren, Hudson, Lee, Leeron, Shira, Adee, Yoni, Gali and Lavee. Shiva was held at the family home until Tuesday.

But, his beneficiaries said, his impact will also live on through what he taught and how he lived.

“Not only will his grandchildren’s grandchildren understand the value of charity, which was his personal goal, but people too who are the recipients … their grandchildren will be talking about Kaylie, the name Kaylie, the word Kaylie,” Mandel said.