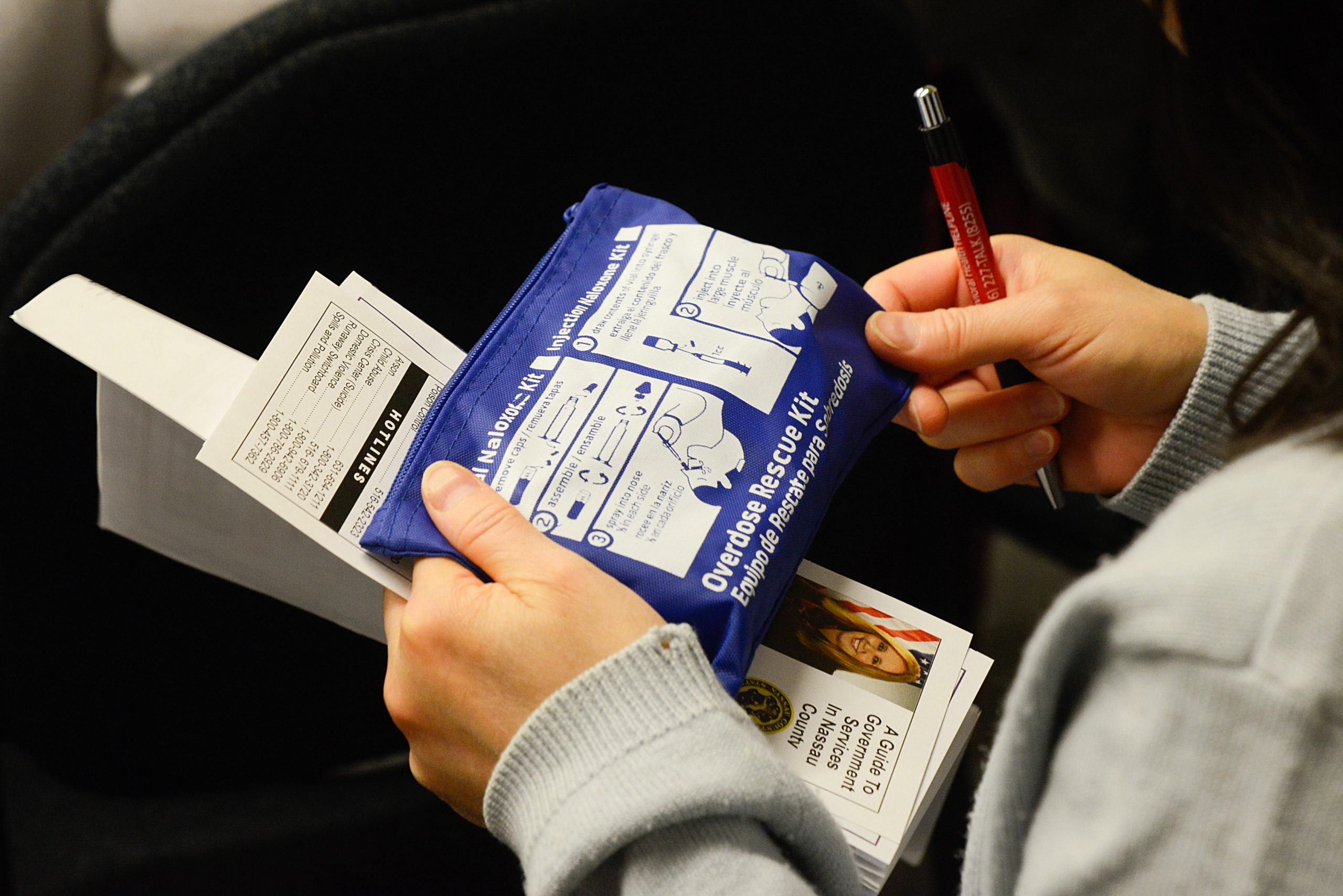

With the opioid epidemic sweeping the country, many law enforcement groups, including the Nassau County police, now have a Narcan kit to revive people who have overdosed. But that is not enough, argues county Legislator Delia DeRiggi-Whitton. That is why she is holding a Narcan kit training session.

“I’m a big believer in being prepared for anything,” she said. “It’s no expense to anyone who attends… I would like to get as many people trained as possible just to be on the safe side.”

DeRiggi-Whitton, who represents Port Washington, Glen Cove and parts of Roslyn, is co-sponsoring the training session with Catholic Health Services and the Port Washington Police Department. The session will be held on Nov. 8 from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. in Saint Francis Hospital’s De Matteis Center Auditorium, located at 101 Northern Blvd. in Greenvale.

Narcan can be administered through a needle or nasal spray and will not harm the recipient, even if it is administered to someone who is not overdosing. In September, 45 people in Nassau County were saved by Narcan administered by a police officer, fire department volunteer or civilian.

Nine people died of overdoses in that period, but September had the fewest deaths and the greatest number of saved lives of any month in the past two and a half years, her office said.

Over the past few years, DeRiggi-Whitton has responded to the crisis by holding a number of training sessions.

“I think we’ve already trained over 500 people,” she said. “I think there should be a kit in every household.”

One big reason she has pushed for these training sessions is that opioid addictions can happen to anyone, and she knows families struck by tragedy.

“A know a family who has three kids, honors students, and you wouldn’t expect it,” she said. “But one of the boys, it started with surgery, and he got hooked on painkillers.”

Some have made the argument that the increased availability of Narcan has made opioid addicts more likely to take risks, knowing that they have a good chance of being revived should they overdose. But DeRiggi-Whitton feels that concern is overblown.

“I don’t think anyone goes in saying, ‘I want to be a heroin addict,'” she said. “Narcan is like wearing a seatbelt. When you go out driving, you’re not going to go hit a tree. This is a very tough thing, you can get hooked very quickly. It’s never guaranteed that [Narcan] will save someone, but it’s one tool that they have.”

DeRiggi-Whitton said that though Narcan will save lives, it will not end the nation’s opioid crisis. That must come from the top in the pharmaceutical industry.

“It is my hope that the medical and pharmaceutical industries are starting to accept some responsibility for the problem and are working to develop less or nonaddictive alternative to opioid painkillers,” she said.