“Build it, and they will come.”

That’s the approach Mineola school district officials are taking to achieve gender parity in computer science classes as they work to integrate the subject more deeply into curricula, Superintendent Michael Nagler said.

Starting this fall, all third- through seventh-graders will complete three coding projects in different subject areas using the kidOYO platform, Nagler said. Students already use kidOYO, which the district introduced in 2015, to complete coding activities on their own.

District leaders want to create a bigger “pipeline” of younger students who go on to take advanced computer science courses in high school, Nagler said. Administrators are betting those bigger cohorts will naturally include more girls, who are statistically less likely to pursue computer science jobs.

“That’s the domino theory — that we’re going to have more exposure, we’re going to have more kids interested, more kids not afraid … to tackle it,” Nagler said.

The effort in the lower grades complements recent efforts at Mineola High School to bolster computer science studies, said Katie Sheehan, one of the school’s two information technology coordinators.

All ninth-graders take a course called “Exploring Computer Science,” which teaches basic coding and computer logic. Students can then go on to take Advanced Placement computer science and eventually take college-level courses through the district’s partnership with Queensborough Community College, Sheehan said.

The high school is also expanding the use of its fabrication lab, or “fab lab,” where students create designs and then program machines such as 3D printers to create them. Eighth-graders are now doing more activities in the lab, Sheehan said, and it will be open for an hour after school starting this fall for students who want more practice.

“I think what we’re trying to do at the lower levels is plant that seed of interest and then nurture that interest through middle school and in the high school,” Sheehan said.

Mineola’s most recent AP computer science class was about two-thirds boys and one-third girls, Sheehan said. That reflects a national gap — while the number has increased in recent years, only 26.7 percent of students taking AP computer science tests this year were girls, according to College Board data.

The disparity continues in college. Some 17.8 percent of computer science graduates in the U.S. are women, less than the average among the wealthy, industrialized countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Mineola administrators are “keenly aware” of the broader gender gap and are “working toward some inventive ideas” to address it locally, the school board president, Christine Napolitano, said in an email.

Officials are discussing an AP computer science class exclusively for girls to encourage them to take more chances and push their studies further, Nagler and Sheehan said. And some students Napolitano met with floated the idea of having senior female students mentor younger ones, she said.

Ultimately, no one can force female students to take computer science classes, Sheehan said, but the district succeeds at giving all students a “vast umbrella of experience.” And having women like Sheehan teach those skills can show girls that they could have a career in the field, she said.

“I don’t think you’re going to see a change overnight,” Sheehan said. “I think that this is something that will come with time.”

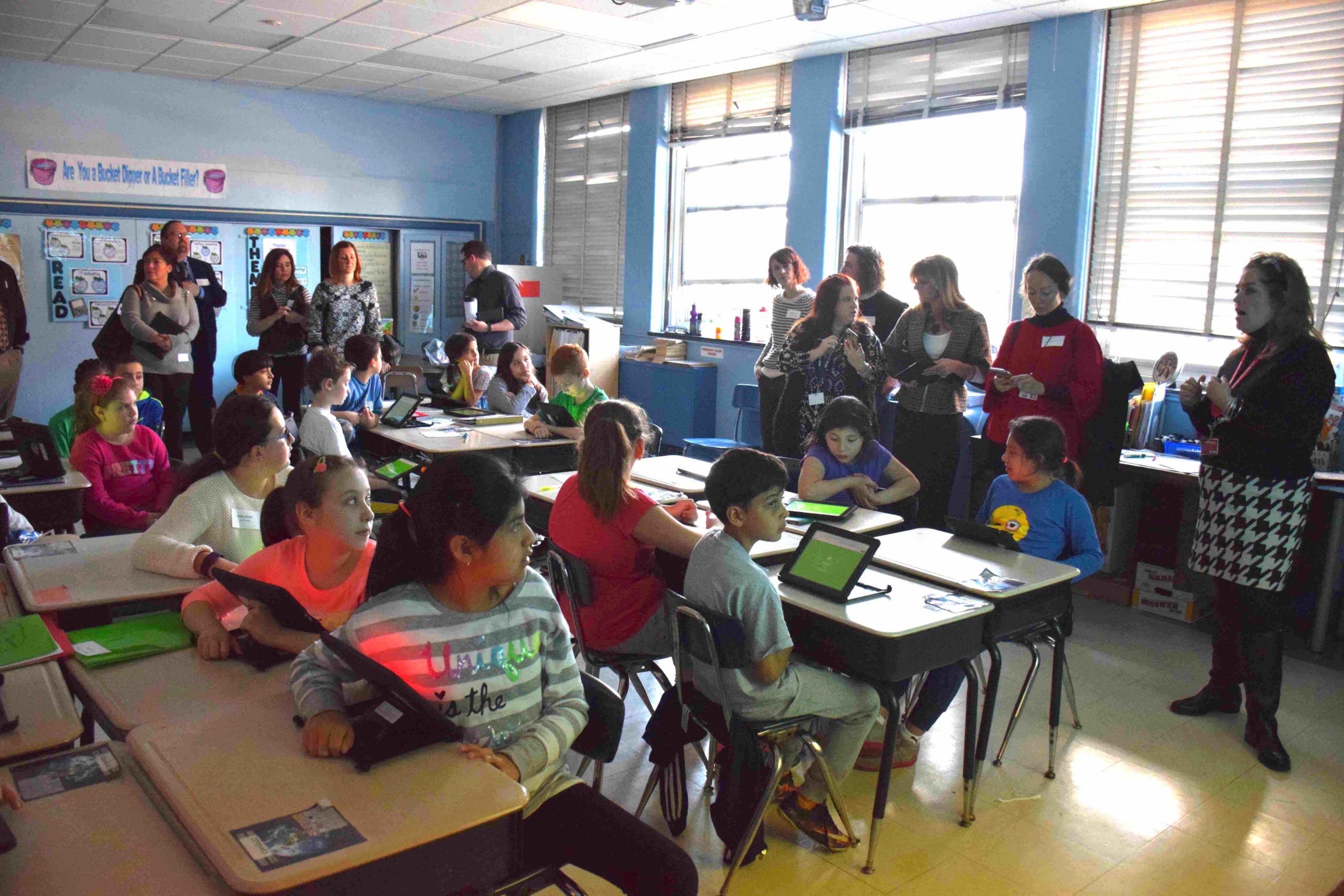

The broad exposure is another way the district has tried to level the playing field by giving everyone a chance to learn with new technology, Sheehan said. Every Mineola student has an iPad for in-class and at-home use, and Nagler said the kidOYO platform offers a “very nimble system” to keep its computer science curriculum up to date.

Requiring all teachers to create code-based lessons will help teachers understand the importance of computer science as well as students, Nagler said.

“The primary problem is the pathway for the field. If you think about it, it isn’t taught,” he said. “So how are we cultivating these learning paths for kids that show them what computer science is and what’s involved in learning it, and then encouraging them to do so?”