On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence, breaking away from the British Empire. But by then, the Town of North Hempstead had already declared its independence.

On Sept. 23, 1775, a group of North Shore residents agreed to break away from the Town of Hempstead.

“The southern part of the Town of Hempstead was mostly British citizens, they liked the status quo and didn’t want a revolution,” said Howard Kroplick, the historian for the Town of North Hempstead.

The northern part of Hempstead, he said, was mostly of Dutch ancestry. Based on gravestones in Monfort Cemetery in Port Washington, Kroplick said that colonists of Dutch descent began settling in the area around the 1730s. These groups settled in Great Neck and Port Washington/Manhasset, the latter of which was referred to as Cow Neck at the time.

As tensions rose between Great Britain and the American colonies in the 1770s, so too did tensions between Loyalists and revolutionaries. In the summer of 1775, the Town of Hempstead signed an oath of loyalty to King George III, several months after skirmishes between colonial militias and the British Army took place in Concord, Massachusetts.

“That broke the back of the northern settlers,” Kroplick said. “They didn’t want any part of that. So the 1775 declaration of independence was a reaction to that.”

“Their general conduct is inimical to freedom, we be no further considered as part of the township of Hempstead than is consistent with peace, liberty and safety; therefore in all matters relative to the Congressional plan, we shall consider ourselves an entire, separate and independent beat or district,” the group wrote in the 1775 declaration.

Among those who signed were Adrian Onderdonck, who would serve as the first supervisor for the Town of North Hempstead, and Thomas Dodge and Petrus Onderdonck, who would go on to fight in the Continental Army.

Kroplick said there are no historical records that he could find that indicated what the reaction was among the leaders in the Town of Hempstead to a northern secession. Nine months after the 1775 declaration was signed, British troops under the command of Gen. William Howe began landing on Staten Island. After a two month standoff, British troops landed on Long Island to attack Gen. George Washington’s position in Manhattan.

The Battle of Long Island was fought on Aug. 27 on what is now Brooklyn. The result was a decisive victory for the British, and Washington was forced to evacuate from Brooklyn and eventually from Manhattan in September.

The retreat of American forces left New York City, and thus all of Long Island, in British hands.

“They took over the major estates in the area and used them to house troops,” Kroplick said. “The Quaker meeting house in Manhasset, that was used to host Hessian soldiers.”

Kroplick said that many of the patriots from Great Neck and Cow Neck fled following Washington’s defeat. Adrian Onderdonck, who was 69 years old at the time, was among those unable to leave.

“He was harassed by the British, but he stayed here and survived,” he said.

In 1783, the British forces evacuated from New York following the conclusion of the Revolutionary War. In 1784, the leaders of North Shore followed through on the declaration that they had made nine years earlier and the Town of North Hempstead was officially incorporated by the state Senate. The border was defined in the document by the “country road,” which remains to this day as Old Country Road.

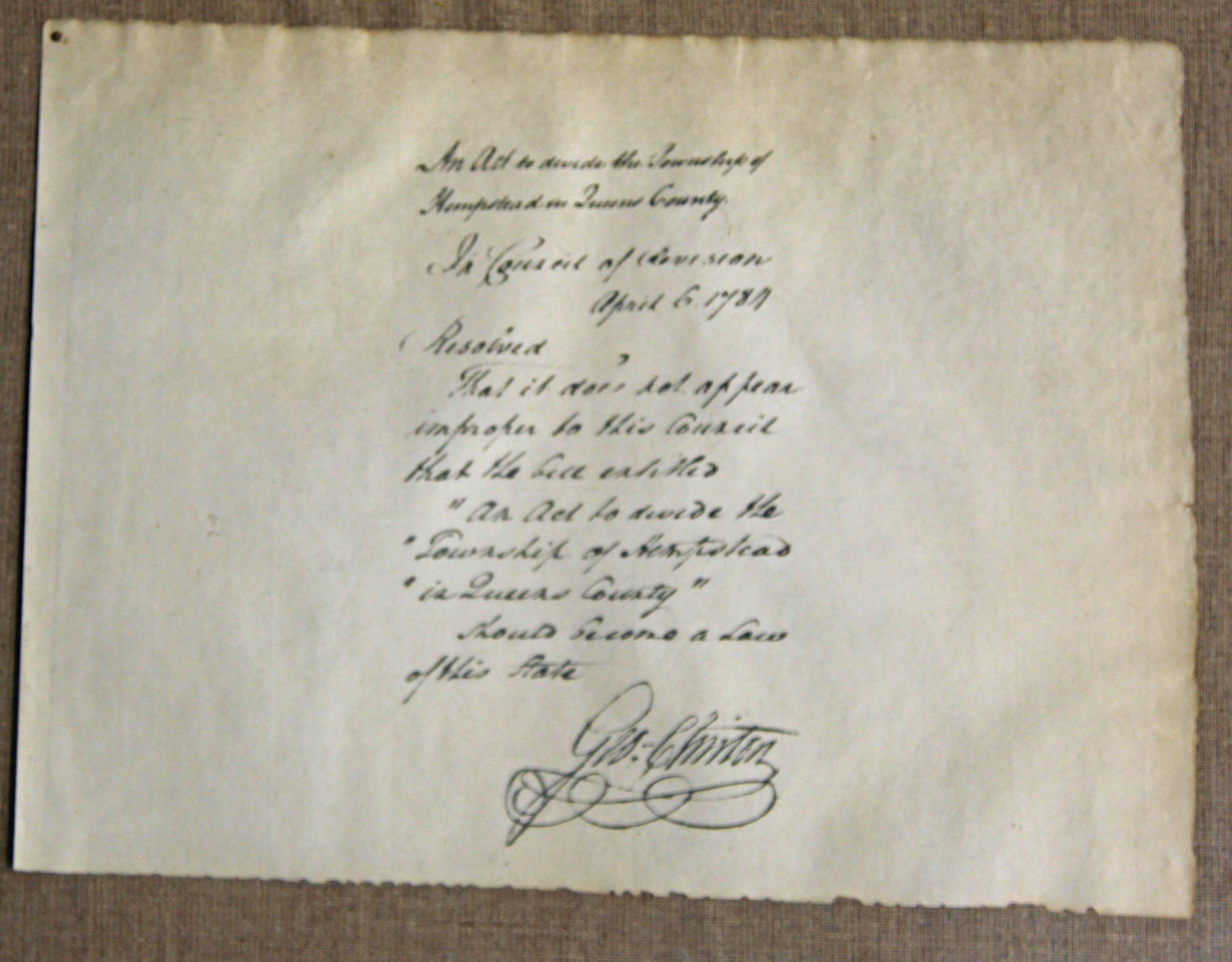

That document, signed by Gov. George Clinton on April 6, 1784, remains with North Hempstead at the Town Hall in Manhasset.