Rivalries bring out the very best in us. Whether it’s as simple as sibling rivalry, as compelling as Roger Maris vs. Mickey Mantle or as complex as communism vs. capitalism, we all grow when we are rivaled.

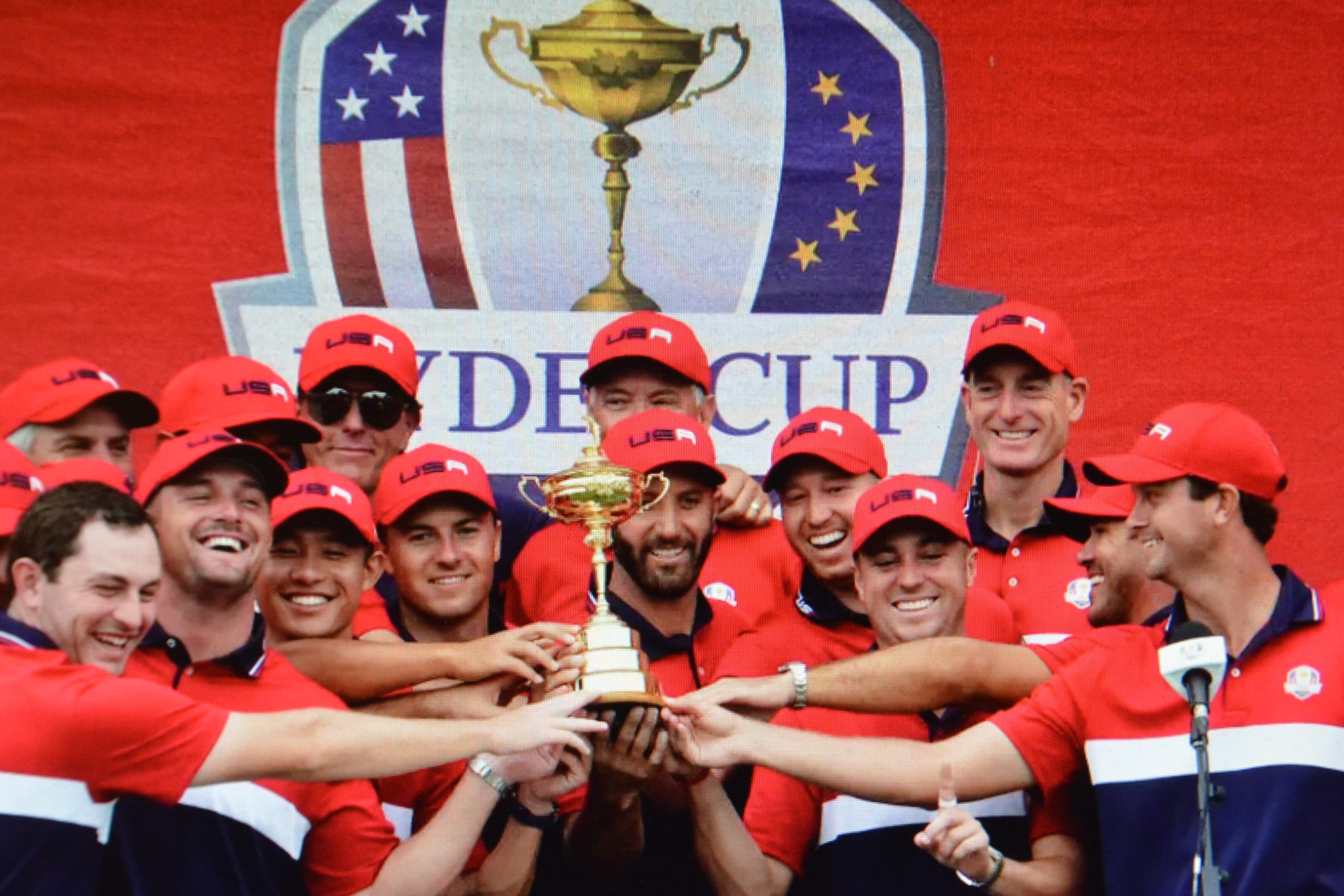

The world witnessed one of the great sports rivalries this weekend at the 43rd Ryder Cup played at Whistling Straits in Kohler, Wis. Led by the likable Capt. Steve Stricker and 12 of the best golfers on Earth, America swept over the European team and won the Ryder Cup with a resounding 19 – 9 win.

Television commentators waxed poetic about how the American team meshed so well, remained focused and played up to expectation. They were heavily favored to win, which added to the pressure faced by each player.

The crowd was highly partisan as it often is in Ryder Cups, the pre-eminent golf event of the year. The explanations of why the U.S. dominated included three elements: 1) the choice of Whistling Straits, which was a very tough venue 2) the partisan nature of the cheering home crowd with very few European fans due to Covid-19 travel restrictions and 3) the youth of the American team with Collin Morikawa, age 24; Xander Schauffele, age 27; Daniel Berger, age 28; Justin Thomas, age 28; and Bryson DeChambeau, age 27.

Compare this with the European players, who included Paul Casey, age 44; Sergio Garcia, age 41; Shane Lowry, age 34; Ian Poulter, age 45; and Lee Westwood, age 48.

They are saying this dominant win will usher in a new era of American golf where youth, aggression and power win the day. Youth, power, and aggression are part of the American character, best described by the French aristocrat and political scientist Alexis de Tocqueville in “Democracy in America” (1840.) De Tocqueville concluded that as a nation Americans were industrious, practical, enterprising, down to earth, materialistic, interested in wealth and essentially non-communal. He observed that we were not very deep and that we showed little interest in art or in other intellectual pursuits.

It has been written that the reason Americans did so poorly in the Ryder Cup matches in the past was because we were too independent and did not bond as a team. Capt. Stricker may have unwittingly discovered the secret formula of how to win this very team-oriented event by de-emphasizing the team aspect entirely, letting the players stick to their own schedules and agendas and avoiding all team speeches and team-building experiences.

American character is independent, non-communal, materialistic, not introspective, not intellectual, very industrious and very hardworking. This is our talent and explains why we are so globally successful, but these traits also reveal our greatest weakness.

As a sport psychologist, I am always interested in observing why athletes self-defeat and invariably this does not stem form laziness or from lack of trying. American sport psychology has little to say about why athletes self-defeat or why they seem unaware of the causes of their own problems on or off the field.

American-style psychology and sport psychology are based upon the work of John B. Watson, B.F. Skinner, Albert Ellis and Albert Bandura and these treatments emphasize self-talk and are practical, quick fix type interventions. They all lack depth and are adamantly against the concept of the unconscious.

Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the unconscious continues to have a profound impact on human culture, but when his theories came to the U.S., our university system reacted strongly by denying his theories and emphasized treatments that attempt to teach the patient to think or to do things differently while naively assuming that the patient is able to follow orders.

This is comparable to asking a patient who has cancer to perform surgery on himself. These American cognitive behavioral treatments all sound good in theory, but sadly they have very little impact on a person’s thoughts or behaviors and even less impact on an athlete’s performance.

The reason for this, as Freud pointed out, is because a person’s unconscious tends to call the shots. The best laid plans of mice and men often go astray not because of bad luck or lack of trying but largely because of inner conflicts and fears that are hidden from view and seated deeply in the dark cellar called the unconscious.

So, in some way, just as there remains a rivalry between America and Europe in the Ryder Cup matches, there is also a rivalry between American sport psychology and European sport psychology, which is now referred to as depth sport psychology.

Despite this year’s victory of America vs. Europe in golf, I predict that the future of sport psychology will be found in methods that explore the athlete’s unconscious and to date the only way you can get into the inner depths of the mind is not with pills or with self-talk but by using the theories of Sigmund Freud, a guy who worked in Vienna and London, both of which are located east of us in a land called Europe.

Americans are tough competitors, practical, independent, and hardworking, but no matter how big your dream is, no matter how much talent you have or hard work you’re willing to expend, you had better be able to find a way to look within and figure out what’s going on the dark recesses of your mind. The greatest rival you will ever meet is not the guy across from you on the playing field or the conference desk but the guy we call the internal saboteur and he lives right in your own head.