A new scoreboard for Williston Park’s Little League baseball field. Resurfaced tennis courts in New Hyde Park. A power generator for a theater in East Hills. Performances for children at Landmark on Main Street in Port Washington.

These projects and initiatives, along with 102 others on the North Shore, have received money from state grant programs through members of the Assembly and Senate.

The lawmakers often promote them with news releases and appear at ribbon-cuttings when they’re complete — sometimes as they run campaigns for re-election or for another office.

Those lawmakers have discretion over who receives hundreds of millions of dollars in grants each year through three programs: the State and Municipal Facilities Program, the Community Projects Fund and supplemental grants to school districts and libraries known as “bullet aid,” according to state legislators, their aides and publicly available documents.

More than $1.5 billion has been appropriated for the State and Municipal Facilities Program alone since its inception.

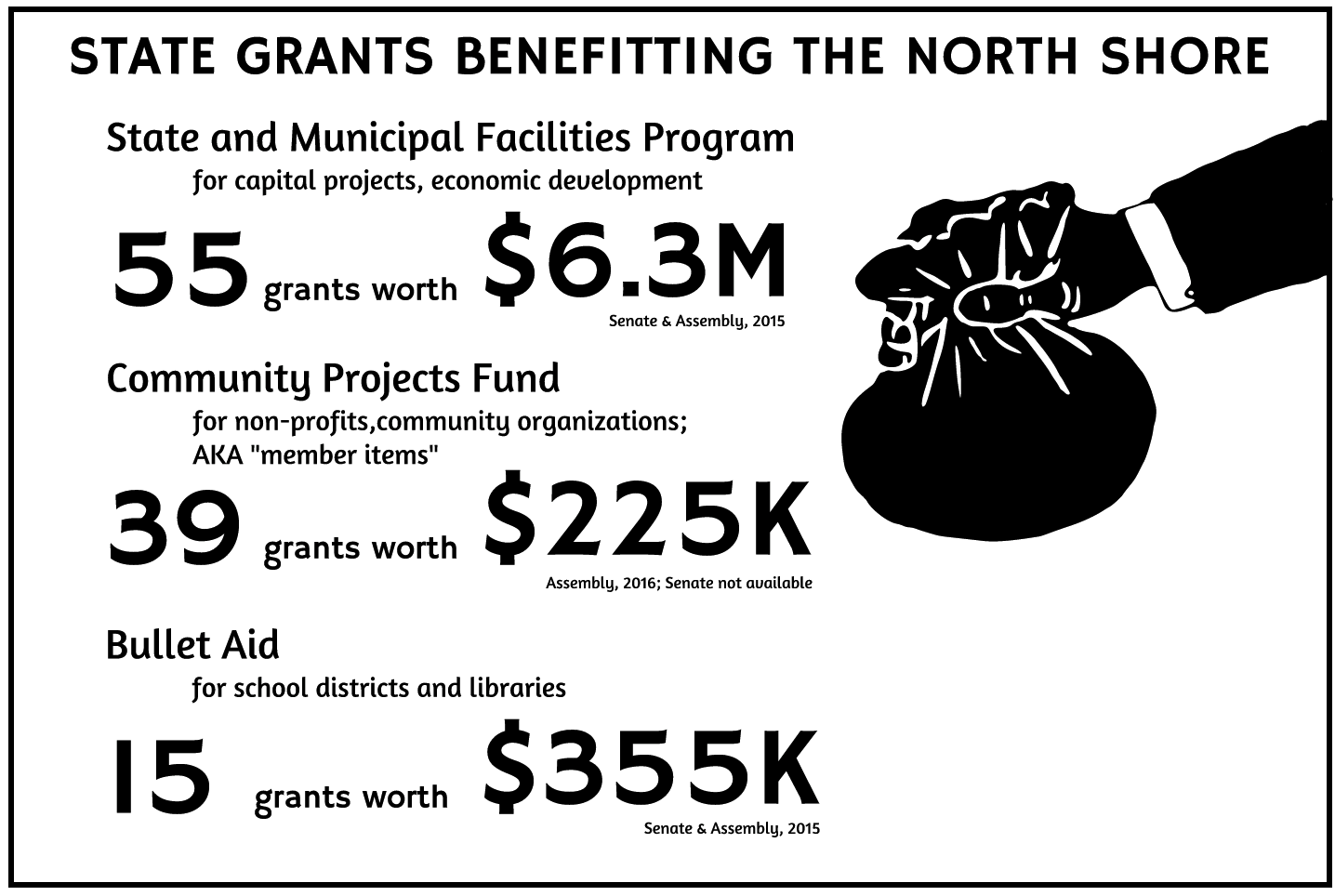

North Shore municipalities and nonprofit groups have been designated to receive at least 109 grants worth nearly $6.9 million since 2014, according to lists published by the Senate and Assembly.

Ranging in size from $5,000 to $350,000, they are meant to pay for projects from after-school programs to road repairs and major construction work at public parks.

Local officials have praised lawmakers for obtaining the grants, saying they provide funding for needed projects for which small municipalities could not otherwise pay.

“Communities rightfully expect their legislators to fight for them and bring home as much state aid as possible, because every additional dollar in aid from Albany is one that doesn’t have to be raised locally,” Chris Schneider, a spokesman for state Sen. Jack Martins (R-Old Westbury), wrote in an email.

But government watchdogs say the grants come from opaque piles of money that are subject to political forces and that lack clear criteria for who can and should receive them.

That means they pose a financial risk to the state, according to state Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli.

“At the end of the day we shouldn’t be doing any of them,” said E.J. McMahon, executive director of the Empire Center for Public Policy, a conservative think tank. “This is not core state priorities. This is political pork.”

North Shore legislators and their aides said the majority leader of each chamber — Democrat Carl Heastie in the Assembly and Republican John Flanagan in the Senate — primarily decide who gets grant money to award and how much.

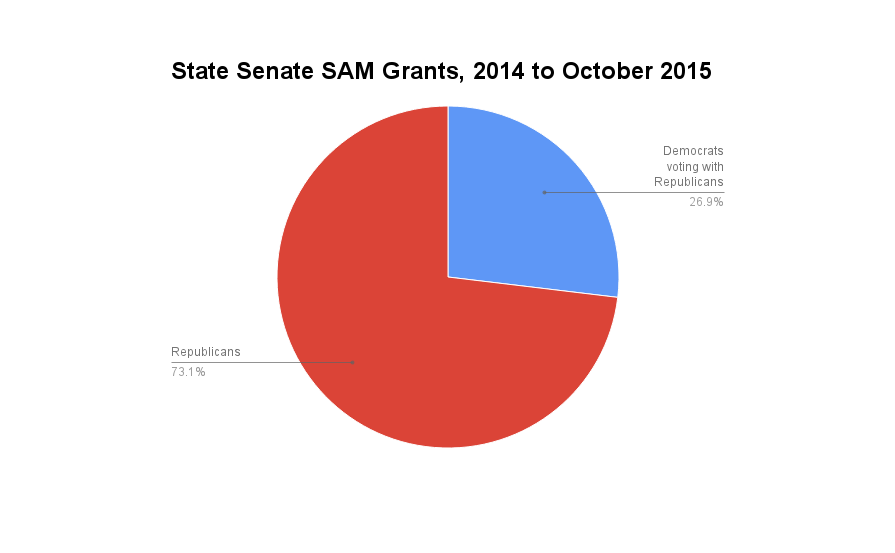

Documents indicate a major partisan imbalance.

Republican senators and Democrats who vote and caucus with them awarded nearly $84.5 million worth of State and Municipal Facilities Program, or SAM, grants between early 2014 and October 2015, according to a list the Senate published last year.

Democrats who are not part of the breakaway Independent Democratic Conference — aside from Simcha Felder of Brooklyn, who votes with Republicans — got none to award, according to the list.

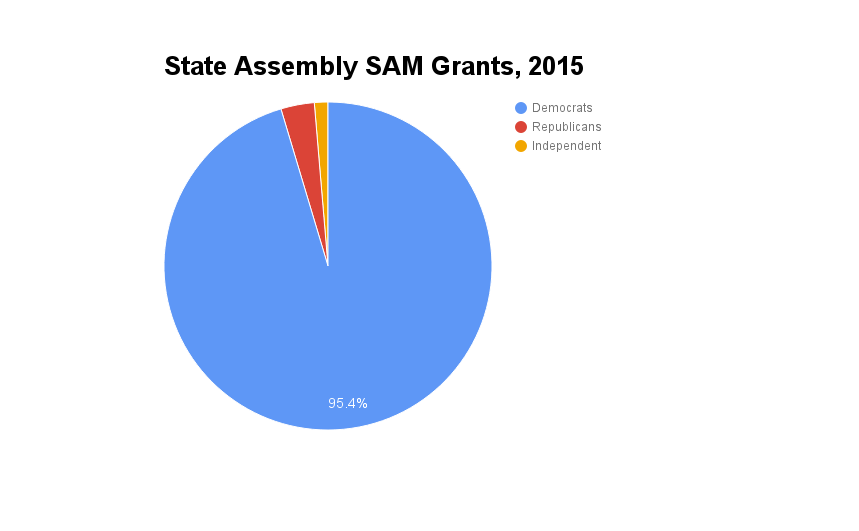

Assembly Democrats gave more than $104.2 million in SAM grants in 2015, according to a list the Assembly published last year.

Republicans got a total of $3.6 million. State Assemblyman Fred Thiele, an Independent, awarded more than $1.3 million.

North Shore Democratic Assembly members Charles Lavine, Michelle Schimel and Michaelle Solages awarded 39 community project grants worth $225,000 this year, according to an Assembly list published in October.

State Assemblyman Ed Ra, along with the rest of his Republican colleagues, got no money to award this year, according to the list.

“I think this plays into all of the concerns that it would talk about with ethics in the Legislature and everything,” Ra said in an interview. “Having the resources, the control, that much at the top is just another thing that the top leadership has to hang over the heads of the rank and file.”

The Senate and Assembly publish some lists of awarded grants on their websites, but spokespeople for both chambers did not respond to emails seeking detailed information about how money is allocated among legislators and the processes for determining who receives grants.

The process for receiving grants is straightforward, according to interviews with state and village officials — municipalities or community organizations send lawmakers a letter saying what they want to do and how much money they need to do it, and the legislator decides who gets funding.

That concerns DiNapoli and officials in his office.

In a May comptroller’s report titled “Unfinished Business: Fiscal Reform in New York State,” DiNapoli proposes more strictly regulating lump-sum budget appropriations like those used to fund the grant programs.

“Details on expenditures – purposes, recipients and other key factors – remain largely outside the State accounting system,” DiNapoli’s report says, specifically referring to the State and Municipal Facilities Program. “… As a result, it is difficult for the public to be assured that the funds are being put to good use in a cost-efficient and effective manner.”

Where oversight is arguably lacking before grants are awarded, it is very much present afterward, state and local officials said.

It takes an average of a year for grant money to be disbursed once allocated as the applications are reviewed by state agencies and the Legislature, said Tara Butler, Lavine’s chief of staff.

Municipalities receive capital grant money as a reimbursement after performing the designated work.

“Whether it’s $500,000 or $5,000, it takes a really long time,” Butler said.

Their partisan aspects may not be pretty, but ultimately the grant programs help North Shore communities and are run in the best way possible, Lavine said.

“If we view this process cynically, which is easy to do, it’s simple to do, then we play a role in undermining democracy, because majority rule is what counts in our families, it counts in our communities, and it has to count in our government,” he said. “There’s no other way to do it.”

A spokesman for the GOP Senate majority did not respond to requests for comment.

Schimel referred two requests for information about grants to the Assembly press office, which did not respond to repeated requests for information over several weeks.

A representative for Solages did not respond to a request to schedule an interview with her staff member who handles grants. The office did send a list of grants Solages awarded in the last fiscal year.

THREE PRIMARY PROGRAMS

The State and Municipal Facilities Program is the largest initiative through which North Shore communities receive state grants.

The state has allocated $385 million to the program each year for four years. Municipalities and other publicly financed bodies can request funding for brick-and-mortar building projects, certain vehicles or economic development projects, according to state budget documents.

Most grants are administered through the state Dormitory Authority, which borrows the money to fund the program.

From February 2014 to late 2015, North Shore municipalities were nominated for 55 SAM grants worth a total of $6.3 million, according to lists published in 2015. The Dormitory Authority reviewed 10 of them as of Oct. 20.

Thirty-nine came from Martins; two from ex-Senate Majority Leader Dean Skelos (awarded to Nassau County), a Republican convicted last year on corruption charges; three from Schimel; five from Lavine (D-Glen Cove); and one from Ra (R-Franklin Square).

The grants have funded large capital projects, such as the $250,000 renovation of the Village of Williston Park’s firehouse and road repaving in the Village of Thomaston, as well as purchases of new vehicles. Fifteen were designated for improvements at local parks.

New money has not been appropriated since 2010 for the Community Projects Fund, which provides smaller grants known as “member items” to municipalities and non-profits.

But some money is reappropriated and distributed to legislators each year.

Three North Shore Assembly members — Lavine, Schimel and Solages, all Democrats — awarded 39 grants worth $225,000 this year using money appropriated between 2001 and 2005, according to an Assembly list published in September.

They went mostly to nonprofit groups, including the Great Neck Breast Cancer Coalition and Roslyn-based North Shore Child and Family Guidance Center, to support social programs and other services.

The amount of money allocated to that program has decreased tremendously since scandals involving the misuse of member item grants, state lawmakers said.

Under the old system, member items could be awarded to almost any organization for almost any purpose with little oversight. That led to several scandals in the Legislature.

In perhaps the most prominent, former Senate Majority Leader Pedro Espada, a Democrat, was convicted on corruption charges in 2012 for funneling member item money to nonprofit groups he controlled.

In the 2009-10 fiscal year, Senate Democrats, who then controlled the chamber, awarded more than 2,700 grants totaling more than $64.1 million.

Senate Republicans awarded fewer than 1,000 grants totaling more than $8.2 million.

More recent information on Senate member item grants, which are now controlled by Republicans, could not be found on the Senate website.

Dozens of so-called “bullet aid” grants also give school districts and local libraries money on top of their annual state aid packages.

The Assembly approved $14 million and the Senate approved $15 million in such grants in 2015.

Lawmakers negotiate the lists of recipients in budget deals each year, Ra and Butler said.

Fifteen bullet aid grants totaling $355,000 went to North Shore schools, libraries and other publicly funded organizations last year.

A POLITICAL ‘HONEY POT’

The Senate and Assembly majority leaders determine who gets grant money and how much — and members of the controlling party get more to dole out than the minority.

Once lawmakers get the money, they ask municipalities and community groups to send written requests for grants, legislators and their aides said. They then review them and decide which projects to fund.

Spokespeople for both chambers did not respond to emails asking how grant funds are distributed among legislators.

Ra said Assembly Republicans received SAM grant money for the first time last year, the first under Democratic Speaker Carl Heastie.

Heastie’s predecessor, Manhattan Democrat Sheldon Silver, was convicted on corruption charges last year.

Ra was given one $100,000 capital grant to award and received $25,000 in community projects money last year, he said.

By contrast, Lavine got $157,500 for the last fiscal year, according to a list Butler provided.

Ra has not received any bullet aid grants since taking office in 2010, he said.

Asked how they are distributed, he said, “I couldn’t even guess.”

“It shouldn’t be, ‘we’re pulling out however many billion dollars for this program and you’re really going to have to peek around to find out where it’s going,’” Ra said. “It shouldn’t be that way.”

The Village of New Hyde Park has a “wish list” of projects it takes to Martins each year that it would otherwise have to fund by raising taxes or borrowing, village Trustee Donna Squicciarino and Mayor Robert Lofaro said.

The village got $200,000 in SAM grant funds to renovate basketball and tennis courts and make other fixes at its Memorial Park in 2015.

But McMahon, head of the Empire Center, said grant programs, especially SAM, are a “honey pot” of political pork-barrel spending that lacks transparency and uses tax dollars from across the state to fund projects that have only local impacts.

“Why in the world is it at any time a priority for the state to put a scoreboard in the village of blank’s Little League field, or to build somebody’s firehouse?” he said. “There’s a lot of these projects in here. Build your own firehouse.”

The lack of clear criteria and oversight for the programs puts them at greater risk for waste, fraud and abuse, officials in DiNapoli’s office said.

The lump sums that fund them should therefore be allocated in a “competitive process with clear, measurable, public and objective criteria defined in statute or by regulation,” DiNapoli’s report on fiscal reform says.

OVERSIGHT AFTER THE FACT

Grants to municipalities and nonprofit groups go through a lengthy vetting processes after the grants are awarded that often take at least a year.

Grant nominations get reviewed by the relevant state agency, then must be reviewed and approved by the Legislature before the agency disburses them, said Butler, Lavine’s chief of staff.

Each grant program has specific eligibility requirements and clear oversight “to ensure that recipients use the funds solely and

entirely for their approved purpose,” unlike previous member item grants that could be awarded for basically any purpose, said Schneider, the Martins spokesman.

Before municipalities get SAM grant payments, they must submit an application for reimbursement after completing the project that includes an itemized breakdown of costs, checks paid to vendors, bid materials and other supporting documents.

For grants administered by the Dormitory Authority, local officials must sign a grant disbursement agreement outlining the terms of the grant and the conditions under which it can be revoked.

New Hyde Park’s materials related to its two grants for the $211,000 park renovation contain hundreds of pages filling two large file folders.

It did not receive the second $150,000 grant until May 31 of this year, more than two years after Martins awarded the first $50,000 grant, and about a year after the project was finished.

The village paid $61,000 out of its coffers for the project.

Robert Lofaro, the village mayor, said the lengthy review was at times frustrating, but he thinks oversight is important to ensuring grant programs are not abused or awarded to politically connected groups.

“Whichever way the discretionary monies work and so on, my concern is that the end result is benefiting somebody, truly,” Lofaro said. “And we feel the money we had received, people in the state, people in the village should feel that we’ve done the right thing with the money that was discretionary that was awarded to us.”

Lavine said an independent body reviewing grant applications would be ideal, but a stricter process could thrust funding for important but sometimes controversial organizations, such as Planned Parenthood, into the political fray.

The current processes give lawmakers flexibility while effectively safeguarding grant money from misuse, he said.

“The bottom line is I am almost positive — I think I am positive — that with rare exception, if I can even think of one, every dollar that I have been able to play a part in distributing to these not-for-profits has been well used,” Lavine said.